Do you ever look back on fandom of yore and think, what was that? One heady summer of lust in my teens, for instance, remains an ever-constant source of curiosity. Back then, I was consuming a cultural diet which included Pride and Prejudice, cliché-laden rom-coms, any romantic film set in autumn, listening to love songs (Anxious Attachment Style Mixtapes) and re-watching the Scream trilogy. The latter was, admittedly, a curveball. On the surface, Wes Craven’s horror film appears far removed from the “happily ever after” trope, though I was exclusively fixated on the blossoming relationship arc between Gale Weathers and Dewey Riley, which was sugar coated with the trivia fact that these characters were played by off-screen couple at the time, Courteney Cox and David Arquette. Absorbing real intimacy funneled through fiction? Now this was catnip for emotional investment.

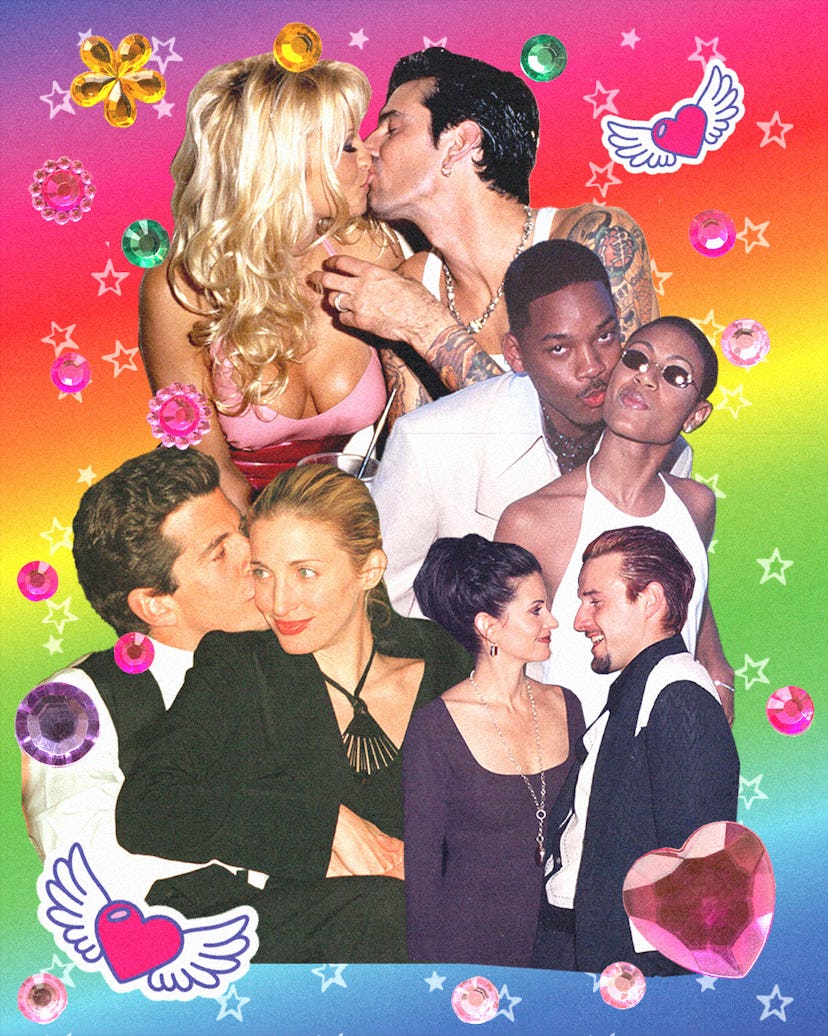

The private lives of public couples still wildly fascinate me. According to Instagram’s “saved” folder, numerous screenshots, and insomniac scrolls through oldloves.tumblr.com over the last year or so there is one absolute specificity—the decade of interest. I am most curious about the 1990s, which also happens to be the decade I was born. Reading the virtual room, this is a majority vote: where demand is high, the supply will follow, from social media’s rising host of visual essays featuring the era’s reigning power couples, to one of the most hyped series of 2022, Pam & Tommy (available to stream on Hulu starting February 2). In essence, the limited series is a Hollywood dramatization of, arguably, one of the most dramatic high-profile unions from this period.

Pamela Anderson and Tommy Lee’s fast and furious relationship is one that, for some reason, we collectively cannot seem to stop revisiting over and over again. Perhaps it’s not the worst thing. “The ’90s was like a coming of age of individuality and self-expression,” James Abraham, founder of the vastly popular Instagram account @90sanxiety, explained to me over the phone. “There was a rawness, a purity of this time that is unmatched. [A time] before people had the ability to share images of themselves—that happened in the 2000s, when people started to connect differently in the more advanced stages of the internet.” People will often DM Abraham to tell him that what he posts “makes them feel good, when a lot of [other] things being shared made them feel uncomfortable or scared or anxious.”

The nostalgia is two-fold. There was a surge in longing for a seemingly simpler time, long before the ‘gram, Google Image, political emergencies, pandemic lexicon, and bleak global news cycles took over everyday existence. Now, meditating on the past serves a practical purpose, offering a blissful reprieve from the muddier present moment. And yet, if you look a little closer at the analog aesthetic that we find so irresistible— the #couple #goals shared, regardless of the fact many have long parted— the allure is, only partly, built upon a need for distraction. In many ways, it speaks to our innermost desires of something lost to be found. Herein lies the missing piece of the puzzle—a brushstroke of everyday eroticism.

For example, take grainy paparazzi images of Anderson and Lee laughing and getting lunch in Malibu (one of Abraham’s personal favorites that he texts me to dissect during our conversation) or fully making out in public (Were they playing it up for the cameras or ignoring their presence? Debatable). There’s also Carolyn Bessette-Kennedy and John F. Kennedy, Jr. walking their dog, kissing in Central Park, grabbing the weekend papers, cycling around New York City; or even professional shoots, such as Annie Leibovitz’s iconic, heavily recycled, picture of a nude Kate Moss in bed with then-boyfriend Johnny Depp circa 1994 (one of my personal favorites). It makes sense that these scenes of flirtation, unapologetic PDA, and connection would hit a cultural nerve today.

Our contemporary fetishized fondness for famous couples of the ’90s, when the 2020s has made us all too aware that we crave the touch of strangers, isn’t merely a mindless preoccupation with time gone by—its pull, I’d argue, is that it draws the eye of the beholder closer to a state of future optimism.

Still, this blurring of boundaries between fantasy and reality is not uncomplicated. These freeze frames of affection— extraordinary people exhibiting ordinariness—feel somewhat attainable, but we also envy them. Celebrity status has long thrived under such conditions. “It’s that coolness factor,” Abraham explains. “You want or idolize what they have.” What was it that they had? That we wanted, or rather, want? It depends on the couple. As if they are characters in a movie or a song, each has a distinctive identity that continues to hold a tight grip on our imagination: the tortured artists (Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love), America’s sweethearts (Jada Pinkett Smith and Will Smith), the indie misfits (Johnny Depp and Winona Ryder).

These double acts remind me of one of literature’s greatest love affairs, between. F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. They are “frequently cited as America’s ‘first celebrity couple’,” according to Sarah Churchwell in the anthology First Comes Love: Power Couples, Celebrity Kinship and Cultural Politics. She writes further, “In 1933, the Fitzgeralds met with Zelda’s doctor to discuss their struggles; Zelda said their marriage had been a battle for as long as she could remember, and Scott replied, according to the doctor’s notes, ‘I don’t know about that. We were about the most envied couple in about 1921 in America.’ Zelda responded, ‘I guess so. We were awfully good showmen.’”

It’s funny when you think about it. We are so quick to glorify ’90s relationship pin-ups and erase, briefly or altogether, the amount of chaos that shrouded their courtships during their lifespans. Between the scandals (two words: sex tape) and public heartbreak (Minnie Driver finding out her relationship with Matt Damon was over on The Oprah Winfrey Show in 1998) to tattoo tributes made and modified (“Wino Forever”) and so on, we are more susceptible to dwell on the good times rather than the turbulent. Could this be indicative of some form of cultural amnesia in which we all purposely paint over the “ugly” parts? Not quite. It may just be that, back then, there was less direct access to receiving information from its starry subjects. There was no social media to more or less steer the narrative ship.

It’s like a game of hide and seek: we are hardwired to be enthralled by that which we cannot see. There is more room to project an illusory vision of what was really happening behind the scenes, based on headlines or glances exchanged. In other words, in the ’90s, we watched these accounts unfold from a far greater distance, where stars were captured in images rather than creating them themselves, adding a lacquer of glamour and mystery to proceedings.

It’s all more intriguing for generations today who have no actual recollection of these romances as they were storyboarded in real time, which is entirely the point. At the heart of any authentic fandom is an unknowability. We hark back to the ghosts of celebrity lover’s past, subsumed by strangers’ lives that exist wholly on our screens, precisely because they mystify us. There is finite data to draw upon if you want to deduce some sketch of a conclusion. Like any memory, nostalgia is a flexible, almost dream-like, state. We’re all just making it up, re-writing the historical script as we go.