When I was 24, I left New York for Paris with no job, apartment, or friends waiting for me in France. I was in a funk, a fugue that lasted for months, if not years, and was directly related to the fact that I wanted to write novels, but could only afford to write marketing copy. The bargain New York was driving—give up your soul in exchange for apartments filled with mice and dust—felt both Faustian and inescapable. Because New York may be a city full of art, parties, ambition, and beauty, but it is, deep in its bones, also a city of money. Everyone always wants more, and without quite a lot of it in New York, life can be unreasonably grim.

So I bought a one-way plane ticket to the best place I could imagine: Paris.

Immediately upon arrival, I could feel myself beginning to thaw. Via a creaky Gaelic website intended for professors on sabbatical, I found an apartment in St. Germain des Pres with high, pale, yellow walls and a Louis XVI armchair and no oven. Friends-of-friends were soon cooking me Palestinian chicken in their kitchens, and crowding tables with me around the Canal St. Martin. I joined the cold, sooty Bibliothèque Mazarine, where I began writing again in earnest.

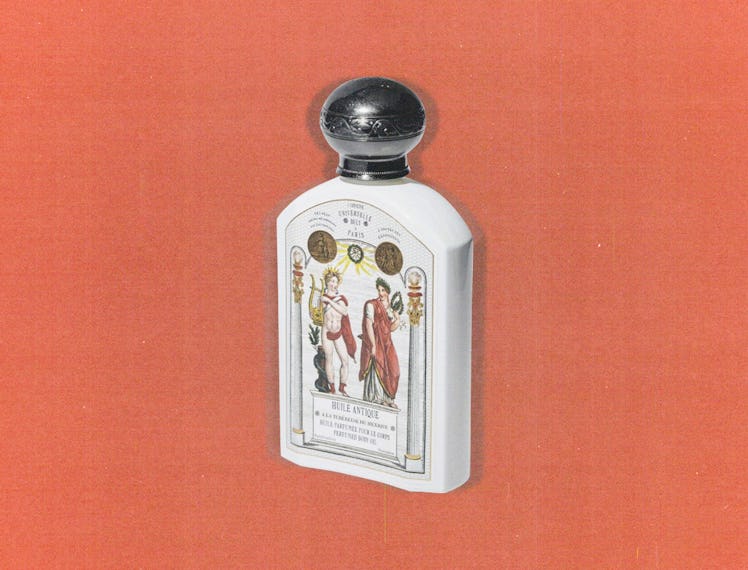

And then there was the apothecary. I needed a toothbrush, so I Googled toothbrush shop near me and headed to the suggested location. I expected the store at 6 rue Bonaparte to be a typical pharmacy, but was stunned upon opening the door to Buly 1803, a Napoleanic-era perfumer founded by a Parisian polymath named Jean-Vincent Bully. Its earliest products were vinegars spiked with citruses, spices, and flowers, which were thought to prevent against the bubonic plague. Buly’s vinegars eventually morphed into a full apothecary’s range, including skincare, powders, and clays. I stood among the shelves that day in awe. Every jar in the store was made of porcelain or glass, covered in high calligraphy, and lit from below like a piece of art. If depression was not caring to brush your teeth, Buly 1803 was in another room, brushing with élan.

The body oil caught my eye on the way to checkout. Huile Antique Mexican Tuberose, the script read on the outside of the glass jar, beneath a sketch of two Greek gods. The oil smelled like night flowers, clove, and a life lived at full density. It came with post-use instructions to “put on a cocktail dress to attend a gala at the Opéra Bastille,” “re-read Ovid’s Metamorphoses,” or “indulge in the pleasure of an almost-nap in the shade of a terrace.” I bought it quickly, before the New York-ish computer inside of me had time to say it was too expensive. That night, I wore it to a party in the Trocadero under a very short dress, and left with an Italian whose name I don’t remember on the back of his Vespa. I realized I was no longer living in grayscale. I had followed the heat and the light to Paris, and Paris had done its job.

Eventually, I left. I went to graduate school in Scotland, and lived for a while later in Los Angeles, which is more in its slowness and shrug like Paris than it lets on. Later still, I moved back to New York for art school, and wrote a novel. And now I live in Brooklyn, with a handful of Huile Antique Mexican Tuberose bottles on my dresser. Friends bring them back for me from Paris, engraved with my name on the box, and when I’m running low, I order directly. Of course, it makes no sense. But neither does love, or art, or any other reasons to remain tethered to this earth. Each day when I smooth it on, it’s a reminder to trust the heartbeat, the id, the ticking clock of a life that is happening and will not happen again. And to follow the heat and the light, always, wherever they may lead.