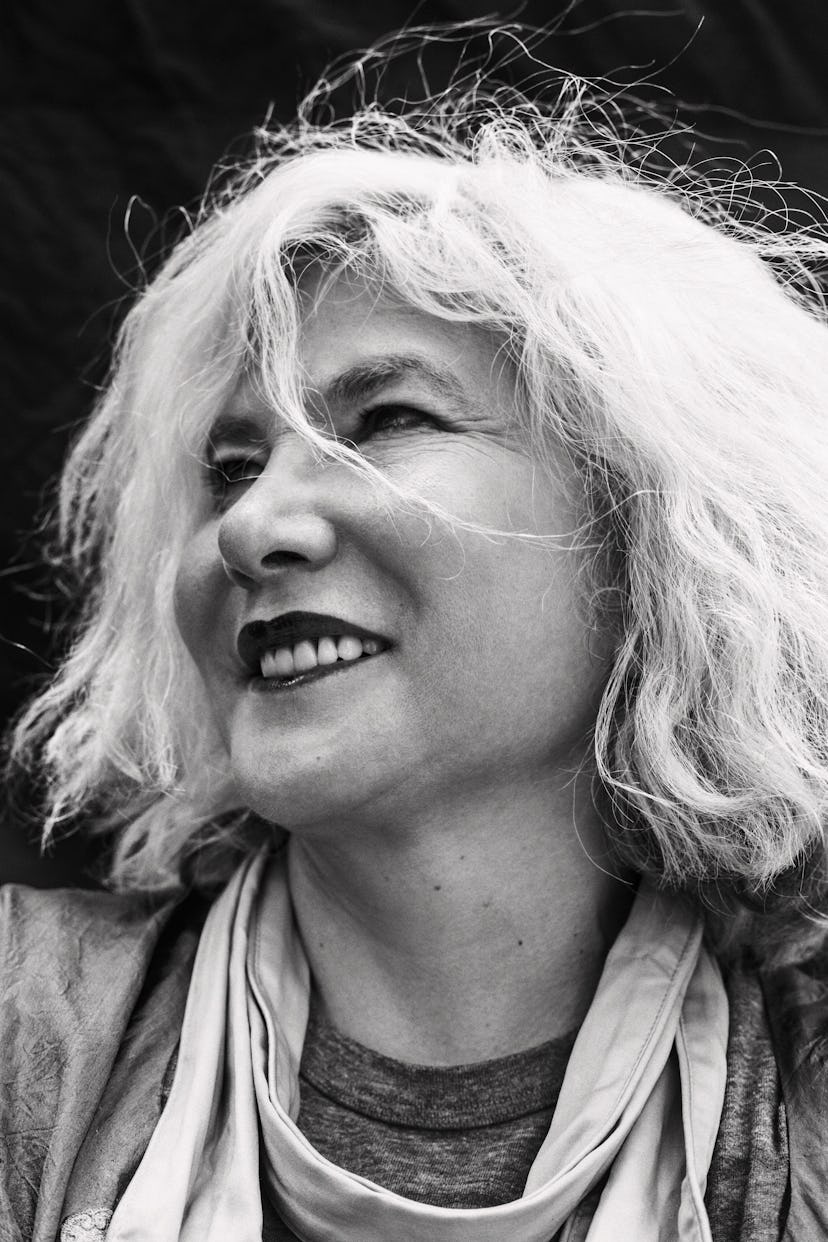

Tama Janowitz is Bored with Glamour

Thirty years after “Slaves of New York,” an It girl in winter looks back at a life on the fast lane that wasn’t always so charmed.

The very best part of Tama Janowitz’s day comes in the morning, after she’s risen and written for a few hours. That’s when she abandons her desk for a nearby farm on the fringes of Schuyler County in upstate New York, where she moved a few years ago. She goes there daily to commune with her beloved horse, Fox. Riding, as she writes in her forthcoming memoir, is one of the last remaining joys in her life.

“Then I come home and writhe,” Janowitz, 59, said when I reached her at home recently. “The writing is exhausting, the riding is exhausting, and then I come home to writhe in self-incrimination and hatred. I call this writing-riding-writhing.” She delivered the line with practiced nonchalance.

Don’t judge Scream: A Memoir of Glamour and Dysfunction, out next week, by its cover. It oversells the glamour part. The dinners with Andy Warhol; the nights at Studio 54 and Danceteria and Pyramid Club; the parties where Janowitz rubbed elbows with Lee Radziwell (“so thin”) and Nancy Reagan (“a lifetime spent not eating”); the dresses made for her by Stephen Sprouse—these are shiny, twinkling flashes of light that have long faded. In Scream, Janowitz is happy to sketch these scenes quickly, at times sharply, but even happier to leave them largely unexamined. (Although she has skewered them forensically in her fiction in the past.)

“Glamour is pretty boring,” she said matter of factly. It’s territory well covered, Janowitz argued, in her journalism, some of which was collected in her 2005 anthology Area Code 212: New York Days, New York Nights. “I can’t bore myself forever by going through the same material.”

And yet the Tama Janowitz origin story—the wild-haired, wacky young woman who became the poster girl of downtown New York almost overnight with the publication of her era-defining story collection Slaves of New York in 1986—continues to seduce new generations of women. But Janowitz never came to New York to seduce; she has always preferred tragedy, and the black humor that leaks out of it if you wring hard enough.

Scream could in fact be boiled down to a series of unfortunate events that have befallen Janowitz in her life; even at the age of 29, when she became famous upon the publication of Slaves, the writer who profiled her for the cover of New York magazine could spot her aura. She noted, almost admiringly, that Janowitz was “a magnet for calamity.” Decades later, she still is.

Not long ago, she fell off her horse and broke her arm. Before that, the horse head-butted her, giving her a black eye. And before that, a squirrel snuck into her apartment and defecated all over her typewriter and an unfinished manuscript. And before that, when she was a teenager in rural Massachusetts, a baby elephant in the zoo where she worked attacked her. And that’s just the adorable animals that have waged war against Janowitz.

Then there are more enduring villains in Scream, like her father, a stoner psychiatrist with an overactive and omnivorous sexual appetite whom Janowitz describes as “lascivious.” When she was 15, he tried to enter her into a wet T-shirt contest at a local bar. After he and her mother divorced—which in small-town New England in the ’60s could disfigure a childhood—he often welched on child support, leaving Janowitz burdened with student loans. Very recently, after there seemed to be peace achieved in the relationship, he decided to disinherit Janowitz from his admittedly modest will.

As she has always done, Janowitz inoculates this string of misfortunes with a steady stream of distant self-deprecation that often tips over into self-immolation. In England, this sort of a book has a name, and a market: the “misery memoir.” In America, where the readership does not thrill so readily to bleakness, trade publications have accused Janowitz, in early reviews of Scream, of whining too much.

“I’ve been taken to town by so many critics,” Janowitz said angrily, adding that they consistently miss the humor in her work. It’s true that after Slaves broke through, few of her books have received the same adoration (although 1999’s A Certain Age, a modern retelling of Edith Wharton’s House of Mirth, was well-liked). At this point, her already thin skin has almost worn clean away. “It’s torture,” she said of unkind reviews.

Tama Janowitz at The Odeon in New York City.

It would be unsympathetic and untrue to say that Janowitz lives for life’s floggings, but tragedy is material. In Scream, the death of her mother, the poet Phyllis Janowitz —whom Tama describes early on as “brilliant” — is the emotional center of the book. Phyllis had always been Tama’s best friend (and just as indispensably, her first and best reader) and after she grew ill in 2011, Janowitz moved upstate from Brooklyn to Ithaca, where Phyllis taught at Cornell, to care for her. During that time, Janowitz did not have the energy to write fiction, so she poured her frustrations—with her marriage to Warhol estate curator Tim Hunt (they are now divorced), her teenage daughter Willow, her career, her meager finances—into memoir.

“Most of my novels are set in fairly painful realities, but my own reality was so painful that I didn’t need to escape into an even more painful one, I guess,” Janowitz said. “I was very depressed writing the book, but I hope it’s funny, too.”

Where she is living now in rural Schuyler County sounds like a fortress of solitude: 40 acres of land, bordered on three sides by the Finger Lakes National Park (“so you can’t build next to it,” she pointed out with glee). When she moved in, she had eight mini-poodles to keep her company—Candy Darling, Gertrude Stein, Petunia, Turtuffe, Moushka, Demon, Fury, and Zizou. Today, only Zizou remains. Unless Janowitz runs into someone at the horse farm, it’s all too easy for her to go days without seeing or speaking to another person.

“It gets lonesome at times,” she admitted. “But I can’t be around people that much. That’s one of the reasons why I couldn’t stay in New York. I didn’t enjoy nightclubs or restaurants anymore. I hated art openings. I no longer used the city.”

But there also the times when Janowitz, once the mascot for a certain moment of New York (she was hemmed in, unfairly, with fellow Brat Pack writers Jay McInerney and Bret Easton Ellis), wondered how she ended up in “this bizarre black hole of the United States without culture,” this region where the recipe for the local delicacy was one box of macaroni, one shaker of table salt, and one jar of Miracle Whip.

“I’ve been stuck, I realize,” she said. “I want to go someplace else. I want someone to invite me to their ranch out West, so I can try it for a few months.” She sighed. “Someplace in the middle of nowhere where I can ride horses.”

The Myth Of Orpheus and Eurydice, Part One: The Wedding