Golden: Gosling

Thanks to The Notebook, women swoon at the mention of his name, but Ryan Gosling wants nothing to do with hunkdom. Instead, he’s working on—and succeeding at—becoming the best actor of his generation.

“Is it too early for a milkshake?” asks actor Ryan Gosling as he slides onto a counter stool at his favorite greasy spoon in Manhattan. It’s just 10 a.m. on an overcast Saturday—for most New Yorkers, too early for anything but a cup of coffee—but Gosling, the next great hope of the movie industry, doesn’t care: He orders a grilled cheese (bacon, please) and a chocolate milkshake. After all, Gosling is something of a renegade, and if his characters, ranging from a Jewish neo-Nazi in The Believer and a latently homosexual teenage killer in Murder by Numbers to a crack-addicted teacher in this summer’s Half Nelson, are any indication, this is a guy who plays by his own rules.

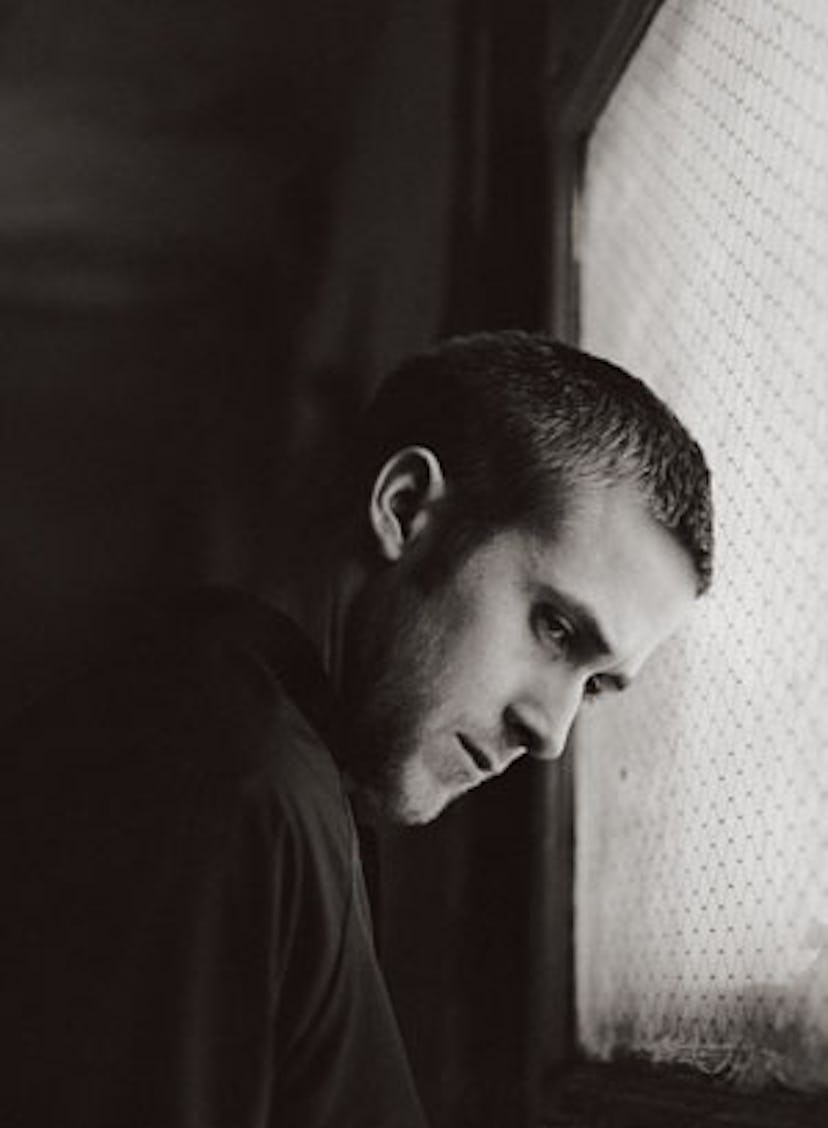

“I read a lot of scripts,” says Gosling, photographed here in Los Angeles in May 2004. “In my opinion, most of them aren’t good or aren’t about people.”

“You want half?” Gosling offers after his first sip of the shake. “It’s delicious.” Gosling’s high-carb, high-fat breakfast is a rather manly choice, and it matches his out-of-style combat jacket, Dr. Martens and paint-splattered black Dickies. (He’s been helping his sister, Mandi, an aspiring musical-theater actress, paint her Hell’s Kitchen apartment.) But it also feels like a holdover from his days on the Mickey Mouse Club, long left in the dust. That’s where he got his start as a teenager, alongside Christina Aguilera, Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake, with whom he bunked in Orlando, Florida. It’s an astonishingly successful crew, and Gosling credits that to the work ethic they learned at an early age.

Still, Gosling was never on a path to selling out stadium concerts. Even then, he knew he wasn’t like the other showboating Mouseketeers, and his colleagues were confused about how he fit in among them. “There were meetings about it. My mother had to fly out [from Canada] and have a meeting with Disney,” Gosling says, scratching his shaved head. He has a gravelly rasp with a tinge of tough-guy New Yawk and a little Brando. “There was one episode where they tried to get me to sing and dance with those guys. They quickly framed me out, you know? I just kind of became background.”

Gosling is no longer blending in with the scenery. With a self-awareness beyond his 25 years and a willingness to defy the conventions of a typical manufactured dreamboat, he has become one of the most admired young actors working today. It’s easy to see why filmmakers respond to him. Many of his peers talk in preprocessed sound bites; Gosling speaks in spontaneous yet well-formed paragraphs, with surprising warmth and a subversive sense of humor. He mentions that he can’t stand the scent of Motorola phones, even though he uses one. He worships Anthony Hopkins, with whom he worked on the upcoming cat-and-mouse thriller Fracture (“I’m the mouse,” says Gosling), because he’s “great at everything he does,” including barking like a dog. “It sounded exactly like a dog,” Gosling says, still dumbfounded. “You could almost tell the breed.”

Since The Believer premiered at Sundance in 2001, the actor has rigorously steered clear of the road most traveled—no superheroes, no summer blockbusters—and that has made him an even hotter commodity. Off duty, he mostly stays out of the spotlight, using his fame to campaign for Darfur or build houses in Mississippi post–Hurricane Katrina. His girlfriend, Rachel McAdams, 29, whom he met on the set of The Notebook—they began dating long after the movie wrapped—is equally adept at dodging the obvious. (She famously walked off a Vanity Fair cover shoot rather than pose nude.)

Gosling insists he had no idea they would become an item while they were filming. “We were together long before we were physically together,” he says. “All I knew is that she was a force to be reckoned with. How I was going to reckon with it, I had no idea. She’s not someone you can ever dismiss or put into any category. She’s many things.”

An elegant if sappy love story, The Notebook was a sleeper hit in the summer of 2004. Gosling and McAdams have never watched it together. Indeed, the movie is so swooningly romantic that if they did, in all likelihood they would have to break up. How could their real-life relationship ever live up to the grand gestures, the sexually charged arguments and the deep and constant confessions of true love?

“Yeah, every time I come home, Rachel screams, ‘Why didn’t you write me?’” Gosling jokes, citing a particularly wrenching scene from the tear-jerker. “Every morning I put arrows outside her bed. And I build her a house every week.” Still, he won’t comment on engagement or marriage. “Ask her,” he says, though when I suggest we call her to do just that, he quickly changes the subject to his reading habits.

Gosling’s idiosyncratic film choices also make him hard to pin down. He followed up The Notebook with last fall’s Stay, a fractured, dreamlike film ostensibly about the aftereffects of a car accident. According to many critics, the movie was not even a noble failure. “We knew going in that they were giving us way more money to make it than we would ever make back, that people were going to ask the same questions that they asked,” Gosling says of the box-office disappointment. “I had a kid come up to me on the street, 10 years old, and he says, ‘Are you that guy from Stay? What the f— was that movie about?’ I think that’s great. I’m just as proud if someone says, ‘Hey, you made me sick in that movie,’ as if they say I made them cry.”

Half Nelson, which was bought for a reported $1 million at Sundance in January, is as challenging and provocative as Stay, though the critical response has been more adulatory. (Manohla Dargis in The New York Times wrote that the film “offers further evidence that Mr. Gosling is among the most exciting actors of his generation.”) Gosling plays an inner-city junior high school teacher who forges an unlikely connection with one of his students after she discovers his drug problem. The film offers no easy ways out for its characters, but it does showcase the actor’s most intense and electrifying performance to date. Throughout the movie, Gosling emits an existential desperation that is alternately repellent and heartbreaking.

“I had no idea what we were dealing with when I cast him,” says director Ryan Fleck, who was initially unaware of the buzz the actor has created in the film community. “There was the Notebook crowd, who told me he was so sweet and dreamy, and the Believer crowd, who said he was going to kick ass.” Gosling volunteered to live in Brooklyn for six weeks before shooting began to get comfortable with the idea of inner-city classrooms. “He’s always thinking, and that’s why the character he plays is so raw,” says Fleck.

Gosling’s particular taste has been wholeheartedly supported by his management team. In the early stages, they helped pay his rent and lent him a car to prevent him from taking a paycheck for a project that might compromise his talent or ideals. (He now earns in the seven figures for a studio movie but cuts his price to scale, roughly $1,000 a week plus gross points, for an indie like Half Nelson.) “I read a lot of scripts. In my opinion, most of them aren’t good or aren’t about people,” Gosling says. “So I keep waiting, and I read and read until I find something that was written by a person about a person. It’s not like I have some real fancy requirement. That’s it.”

Gosling responded to Half Nelson because the characters were his idea of complicated. “They’re constantly crossing boundaries that they shouldn’t cross,” he explains, beginning to draw parallels with his own life. “They’re messy and weird, and what is it that you want from these people and what is it they want from you? Are you just passing time together, or are you trying to learn something? What is a friendship? I have great ones, but I don’t understand them all the time.”

One of those relationships is with photographer Dan Winters, who is 18 years Gosling’s senior. The two met through a friend on a beach in Tybee Island, Georgia, in the summer of 2001. Within five minutes they were sharing their mutual appreciation for Linda Manz in Days of Heaven. “You can’t geek out with a lot of people about Linda Manz,” Gosling notes. “So we became best friends.”

Almost immediately, Winters began photographing Gosling. At first, it was a great way to hang out—they’d go do some graffiti by the Los Angeles River and click—but the work soon became an extended portrait series. The photos that accompany this story are from that collection, one that Winters hopes to continue for as long as the pair remain friends.

“There’s a level of artifice that does not exist in these photographs. They’d be very different if his publicist was there with hair and makeup,” Winters observes. The journey has allowed him to watch his friend mature over the years: “Ryan looks like a different person every time we shoot.”

After filming Lars and the Real Girl, an independently financed feature about a man who has a strange relationship with a blow-up doll, this fall, Gosling’s next step will perhaps be his riskiest yet. In 2007 he hopes to direct a screenplay he has written. He doesn’t want to discuss what it’s about—just that it will feature nonprofessional child actors. He’s well aware that, given the way he scrutinizes (and sometimes trashes) the scripts out there, he’s leaving himself wide open to criticism.

“I’m not saying what I’ve written is a great script,” Gosling admits. “Anybody could write a bad script, and I’m one of them, you know? But I’m not making a script, I’m making a movie. I wrote a script, but I really drew a map of what the trip is going to be. Anything I could capture by getting real people together to behave honestly with one another is way more interesting than something I could conjure up.”

In an interview last fall, Gosling said that he’d never direct a film. Nowadays he’s less likely to predict the future, least of all his own. “I don’t know that anyone really knows how to do this,” he says of making movies and, one supposes, life in general. “We’re all just trying to make our way through it and to find a way to be ourselves and to not get stuck.”

“I don’t know where the road will take me exactly,” he continues. “But I have some things to do here first before I’m done.”