Stylist and Punk Iconoclast Judy Blame Looks Back on His Genre-Defying Career

Even with a career in fashion so protean that he’s now getting the retrospective treatment at London’s ICA, Blame is still keeping it real with a new DIY zine—though his idea of a zine features work by Juergen Teller and Nick Knight.

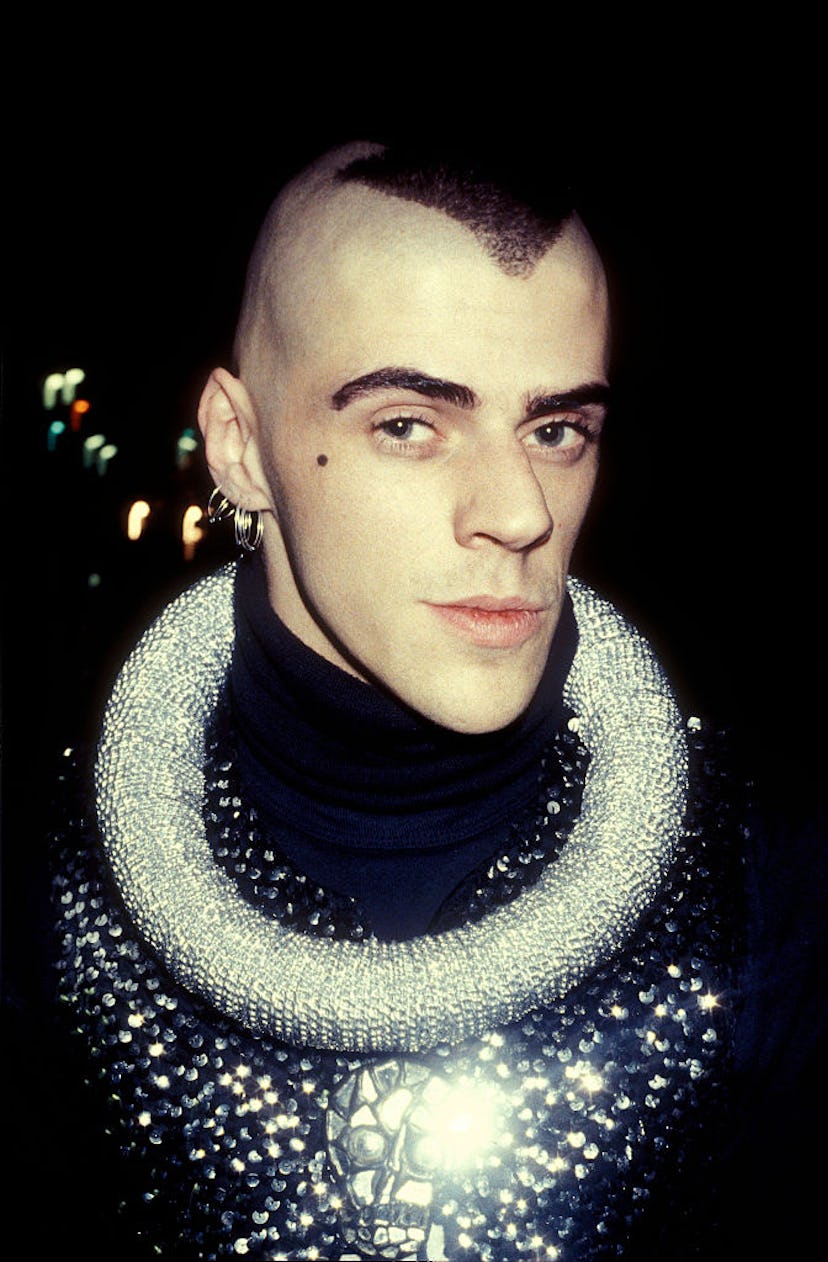

Though he’d been going to London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts for as long as he could remember, Judy Blame initially wasn’t too keen on the idea when the museum approached him last year about a solo exhibition on his decades-long career. The hesitation was mostly because Blame—equal parts stylist, jewelry-maker, art director, and overall punk iconoclast—has just about as much trouble defining his career as the general public does. But if his first name, which he adopted once he’d run away to the nightclubs of London at 16, is any indication, Blame should be fine with resisting classifications, and the public—or at least those in punk’s heyday in London—has taken his lead. Once free from the small town of Leatherhead in Surrey, he became a hit with everyone from Rei Kawakubo to Ray Petri, and was soon helping then-nascent talents like Björk and Alexander McQueen get on their feet. Today, in his mid-50s, Blame’s still hard at work—he’d just done a shoot in London and was waiting to return samples to Gucci when he paused on a recent morning to look back on his career, new zine, and ICA exhibit, which is up until September 4th.

Did it ever occur to you that you might have a museum show?

I never thought about it, and when they first asked me, I was like, “Are you sure?” [Laughs.] I mean, I’ve always been to the ICA for as long as I can remember, but it took me a couple of months to get my head round what to put in it, because I do jump around from fashion, music, graphics. It was quite difficult to kind of find a thread that joined it all together. So it was just trying to find a way where it just didn’t look like a big confusing mess, you know?

When would you say your career first started?

When I first moved to London when I was really young, right, that was ’78. It was a very mad time in England, kind of like the punk days. Everyone was experimenting with what they wanted to do, and I was just a green kid that ran away from home. It took me a while to educate myself with the things that I liked, and then gradually, especially in the early 80’s, I started meeting people in the nightclub scene and the Blitz and the New Romantic after the punk time. I’d always been interested in fashion, so I suppose that was my in. I think the first work we all did was inventing looks for ourselves and going out to nightclubs. [Laughs.] I know that people don’t see that as work, but it was kind of like homework, I suppose. There was a lot of big competition going on when we went out. It was all people like Steve Strange and Boy George, so we were all busy inventing our own kind of personas. And then gradually from going out, I started meeting a lot of people in the fashion business—people like Susanne Bartsch from New York were really encouraging, or the young British designers at the time, people like Stephen Jones. It was a very fertile kind of arena, and we were inspired off each other, I think, a lot of that generation.

So what did you end up deciding was the common thread?

It’s funny, because I’m not a big nostalgia person. I use it as a point of reference, but I’m always kind of moving on to the next thing. So I suppose the common thread was the happiness that I’m still alive doing it. [Laughs.] And I did notice certain things in the work did recur, like that my things can tend to be a bit thought-provoking, or I’ve been using string for 25 years now, and I’ve been using safety pins since ’77. What I wanted the show to do is illustrate how I put ideas together, and so it goes from the materials to my inspirations to physically making something with my hands. Often, making jewelry can spark off a photograph or an album sleeve.

I’m very kind of tactile in the way I put the ideas together, and I wanted to show the thought process in quite a physical way to the young people of today that are kind of unused to threading a needle, not looking at the computer screen. That’s why I called it “Never Again,” because people don’t really put their ideas together like that anymore. It’s more likely to be a mood board, whereas I’m kind of from the generation where you made something to illustrate your idea, you didn’t just cut it out of a magazine. And I think it worked. I was a little bit nervous about it; I was going, “Am I still relevant, doing it like this?” But my favorite thing of the opening, a young fashion student came up to me and just went, “That was really inspiring, Judy, I just want to go home and make something.” To me, that was the best kind of credit that it got, really.

Jewelry, courtesy of Judy Blame.

You’re quite imaginative when it comes to materials, too. What are some of the least conventional you’ve used?

Well, when I first started, I suppose I had a budget thing. We weren’t that rich but we were really creative, so I always used to make things that were accessible to me. That’s what made them different, that I wasn’t always using, say, a traditional jewelry material. I would use something I found and decorate myself or someone else with things from my immediate vicinity. You know, I do love a piece of string, and I love hand-sewing. I find it very therapeutic. I love a good button, so they always crop up. But it can be anything. At the moment, I’ve been collecting little plastic bottle tops. I haven’t quite got there yet, but I will think of a recycled idea with that. Because I’m not classically trained in anything, I kind of use my gut instinct, or it’s about the pure visual of it. It’s quite organic, the way I do it, it sounds really corny to say that, but it is how I do it. [Laughs.] I like to touch it and feel it and hold it and sew it. I get a lot of pleasure out of making something physically with my hands, and I think that’s why I’ve never got bored with it, because I’m forever looking for something else.

Is that partly why you made a zine to go along with the exhibition, too?

I wanted a way where people could walk out of the show with something about it, so I thought about how what inspired me when I was a young person to get me ass off the seat and do something was really fan zines from the punk era. That’s how we used to communicate a lot then about music and people. So I thought, why don’t we do a fan zine, but like for now? I went back through all my boxes of all the ephemera that I’ve collected for years, and we took out certain images that mean something to me personally, and just put it together in a very basic, kind of fan zine way. It was just something the kids could take away.

Inside Judy Blame’s ’80s-Inspired Punk Fan Zine

We did one like a newspaper, and then a really beautifully printed one with Michael Nash, who does my graphics, and where my godchild Isaac who helped put it together works. He was born prematurely in St. Mary’s Hospital in Paddington and had to spend the first two months of his life in an incubator. And then I found out they were looking to do up their pediatric ward, and I happened to be in Adidas borrowing clothes for a shoot and I mentioned I was thinking of donating the proceeds to St. Mary’s, and Adidas ended up helping with the printing. It was very much a family affair, and it was from the heart, with little scraps of things and slogans that I’d always used through my career. And a lot of the pictures have never been published. Juergen Teller came and photographed Neneh [Cherry] once, but the record company didn’t like them back in the early ‘90s, so they were never used. And then I have a print from Nick Knight of one of my mentors, Ray Petri from the Buffalo movement; contact sheets from Glen Luchford from an old shoot that I did, and then we just had some tear sheets. It’s just little snatches and memories of people and times that I really enjoyed.

__Magazines have also been a huge part of your career, especially i-D and The Face. Which of your shoots still stand out?__

Well, there were key points in my life that I put into a fashion editorial context, so they were quite good things to start with for the show. But I wasn’t used to putting things on walls—I’m used to putting things on people, so once I’d put those up and gone, oh look, that pollution shoot I did for i-D was a really important one for me, then I could almost make the tear sheet 3-D by setting up all the black jewelry that I’d made, so people can kind of walk into my ideas. Then there’s a Face editorial that I shot with Jean-Baptiste Mondino and it was very much on a punky scene, so I could kind of put that era of my life from the mid-’80s into it and go onto the shop we used to have called the House of Beauty and Culture when I was working with some designers like Christopher Nemeth and John Moore. And then I turned round and it was like, what else was I doing then, it was a big music part of my life, I was working with Neneh Cherry and Björk and Massive Attack, so I put a bit of that into it.

I mean didn’t put everything in it—I didn’t realize I’d done so many things, to tell you the truth. [Laughs.] Because my work is slightly different, you kind of attract a lot of people that are different, or who are part of the same kind of scene. With Björk, she just happened to be with a record producer that did her first album that was a big friend of mine one night, and she knew that I’d helped Neneh out doing her things, and just said, “Would you come and help me do a photo-shoot with Jean-Baptiste Mondino?” And I loved the record, and I said of course.

Images courtesy of Judy Blame.

You’ve also worked quite a bit with Terry Jones, who worked on W‘s September issue. What are some of the more memorable projects you’ve done with him and i-D?

The brilliant thing about Terry Jones is his enthusiasm. Back in the day when we used to do i-D, you could drop by the office with quite a left-field idea, and if you were passionate about it, Terry just used to turn round to you and go, “Do it.” The classic example is I did a shoot on pollution, and I made all of the models look like the birds being pulled out of the sea when there’s an oil disaster or something. Now, any other fashion editor would have gone, “You’re mad, I’m not interested.” And it could have all blown up in my face, but he saw it through to the end with me, and it really made a difference to the way people look at me and looked at the content of a fashion page. And then another shoot, I said, “Terry, I want to do something on the homeless people.” We used all these [John] Galliano clothes with newspaper, but it was such a thin line. We made it about people because it was too hard to illustrate expensive clothes to look homeless.

Do you think you ever crossed that line?

Well, that particular homeless shoot was very difficult, because it was something that I worried about and I couldn’t quite make it work. With the pollution thing it was very direct and like a protest, whereas the homeless thing really became about the sensitivity for the people. It was so hard, and I remember I did six days of shooting with Juergen Teller, and we still weren’t getting it. So that’s when we went towards all of the beautiful faces. We made it more about people, like family, rather than people with nowhere to live. I felt I wasn’t successful in my original idea from the editorial, but the editorial was successful in the end because we made it about people rather than a theme. And I think that’s the only time. Everything else, it’s like, I like to get people looking at your work to think. If you can get them attracted by the idea, and then also get them to think about it, I mean, that’s the battle won, as far as I’m concerned.