Inside Zaha Hadid’s Final, Fashion-Futuristic Exhibition in London

“The Extraordinary Process,” featuring designers like Iris Van Herpen and Stephen Jones, shows that even in death Hadid is still shaping the future.

Last year, Zaha Hadid met with her design partner Patrik Schumacher and the brains behind what would be a new gallery in London, Maison Mais Non, to work on an exhibition about the future of fashion that wouldn’t be just a standard, static setup of existing clothes. But before she could dive into the specifics, the legendary architect unexpectedly passed away, leaving Schumacher and the curator she’d chosen, Lou Stoppard, to carry out that vision.

“It was done in a very respectful way,” Stoppard said of how she and Schumacher proceeded with “The Extraordinary Vision,” which is now up at Maison Mais Non’s newly minted Soho space until November 16. Case in point: There’s what’s practically a shrine to Hadid by the milliner Stephen Jones — an installation composed of a bench of her design, topped off with some of the Issey Miyake fabric she so often wore, and a giant floating version of one of his hats, which rotates above visitors who sit underneath.

Jones was a natural choice — Hadid was his friend, as well as his client — though not all of the nine designers featured had been acquainted with the late architect. Stoppard and Schumacher selected those they thought aligned with Hadid’s style, past work, and forward thinking, and therefore would not head in the direction that Hadid was keen on avoiding: just another buzzy future-of-fashion-related exhibit or book. Rather than showcasing existing work, Stoppard and Schumacher enlisted the designers “to think about what fashion could be,” Stoppard said.

Inside “The Extraordinary Process,” the Late Architect Zaha Hadid’s Final Exhibit

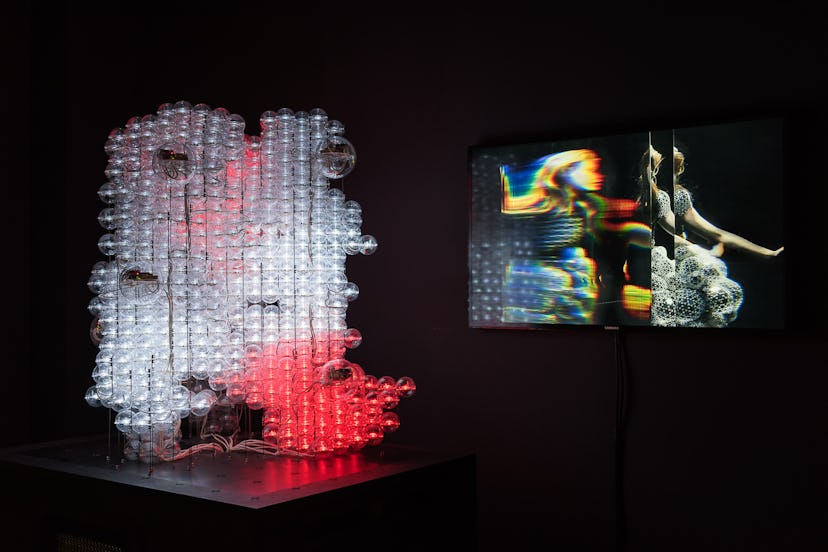

That meant, of course, that the likes of Iris Van Herpen were tasked with working with technology that hasn’t been invented yet. They worked around this conundrum with a little help from Design Research Lab, now helmed by Theodore Spyropoulos, but first founded by Schumacher, the principal of Zaha Hadid Architects. London designer Nasir Mazhar, for example, paired his hat made out of microphones with touch-sensitive robots visitors are free to (gently) provoke. (It’s part of several interactive features Stoppard worked to include at the advice of Hans Ulrich Obrist.)

Peter Do, on the other hand, turned to the knitwear company Stoll to produce a series of garments made of the same yarn that he imagines future denizens could simply download for an at-home machine with ease. It’s an idea that goes back to the idea of fashion’s more utilitarian capacities, something Stoppard points out the industry rarely considers outside of sustainability. “I think we have quite low demands of our clothing, particularly with improving or helping your life,” she said.

For many, like Mazhar, thoughts of the future centered around more fraught issues like privacy. The designer Phoebe English, for example, confronted her anxieties by thinking up clothes that could protect you, ultimately producing a shell out of plastic and calico that she imagined as a sort of safe space – precisely what, in a way, the gallery has become for Hadid’s own unrealized models and propositions for both fashion and architecture, showcased for the first time amidst the robots and 3D prints.