Independent Spirits

This year, directors Danny Boyle, Gus Van Sant, Darren Aronofsky and Mike Leigh showed the industry (yet again) how to make a great movie outside the studio system. They tell W how they did it.

On a warm night last fall, crowds of movie fans pressed against police barriers outside the Castro Theatre in San Francisco, and dozens of photographers strained toward the celebrities making their way down the red carpet, among them the Oscar-laureate leading man Sean Penn, the impossibly handsome breakout star James Franco, the major young acting talent Emile Hirsch, the cult director Gus Van Sant and even the host city’s Kennedy-esque mayor, Gavin Newsom. “Half of Hollywood is here tonight,” said one astonished industry veteran, spotting such pillars as CAA chieftain Bryan Lourd and Steven Spielberg’s longtime producing partner, Kathleen Kennedy.

The occasion was the world premiere of Milk—Van Sant’s biopic starring Penn as gay San Francisco City Supervisor Harvey Milk—and the attendant hoopla was meant to create buzz around a potential awards-season contender. Even before its release, Milk was emerging as a favorite in Hollywood’s year-end prestige race, the annual competition for grown-up audiences and Academy voters that begins after Labor Day and culminates on Oscar night, and the San Francisco party sounded the opening salvo of a well-organized, well-funded campaign.

But more striking than Milk’s storyline—or even the spectacle of its butch Hollywood actors slipping into fey San Francisco characters—is that it got made. The film came to life after screenwriter Dustin Lance Black gave his script to Van Sant and the director said he’d like to shoot it. Partially financed by Groundswell Productions, a company headquartered in Beverly Hills far from any studio lot, Milk’s entire $20 million budget would not have been enough to buy the above-the-line talent in Paramount Pictures’ $175 million The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, starring Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett, or Baz Luhrmann’s Australia, a $130 million epic for 20th Century Fox starring Nicole Kidman and Hugh Jackman.

Although almost every fall season sees some quirky crowd-pleaser or critics’ favorite break through the general din of the studios’ heavily marketed blue-ribbon releases—remember 2007’s Juno?—this season a host of small, independent films are making big noise. Like Van Sant, Danny Boyle, Darren Aronofsky and Mike Leigh have all swapped generous budgets for wide creative freedom to make the kinds of movies that would baffle the studio bean counters. Compared with grandiose productions like Australia that are backed by transnational media conglomerates, this year’s indie favorites are practically handicrafts.

Even with Penn set to star, Milk “barely got a go,” says Van Sant, recalling how when he first started looking for money, the entire Milk team consisted of himself, Black, producers Dan Jinks and Bruce Cohen (Oscar winners for American Beauty), and Penn. “With no Sean, that ‘barely’ might have turned into a ‘no.’”

And if you think a film about a murdered gay politician is a stretch, try Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire, which makes extensive use of Hindi dialogue and stars actors with unpronounceable names. Yet giddy reviews and brushfire word of mouth generated phenomenal box office returns in the first weeks of its release. (In December the National Board of Review named Slumdog its movie of the year; the film also earned a Golden Globe nomination for best picture and a nod from the Los Angeles Film Critics Association for best director.) Leigh’s Happy-Go-Lucky, made by a director so fiercely independent that he likely refuses to speak to Hollywood studio executives even by phone, also features no-name actors and an English working-class milieu. It, too, has generated Oscar speculation owing to a mesmerizing lead performance by Sally Hawkins, who won a Golden Globe nomination. Aronofsky’s The Wrestler stars once infamous has-been Mickey Rourke—a suicidal casting choice by conventional Hollywood thinking. Aronofsky was told repeatedly that Rourke was too “unsympathetic” to headline a film, with one executive adding that the actor had already used up his comeback shot in 2005’s Sin City.

“Once you decide to do something with someone like Mickey Rourke, it is pretty near impossible,” Aronofsky acknowledges, explaining that he nonetheless wanted Rourke, with his bullish body and volatile emotions, from the outset. “In fact, every single financier in the business said no to us.”

Finally, French production company Wild Bunch gave Aronofsky $6 million. (“Leave it to the French to understand Mickey Rourke,” he says.) Still, the measly budget required compromises: Rourke accepted a $100,000 salary, and Aronofsky worked for scale and agreed to a tight 35-day shooting schedule. With no money for extras, Aronofsky relied on one of the film’s producers to rally real-life wrestlers and fans for crowd shots in New Jersey; for another key scene, the director had to shoot at a grocery store during normal business hours because he couldn’t afford the cost of shutting it down. But by having Rourke interact with actual customers at the deli counter, Aronofsky made a virtue of financial necessity, creating a quasi-documentary feel that is one of the film’s strengths.

“When movies are made outside the studio system, there’s such an authenticity to them,” says Peter Rice, head of 20th Century Fox’s specialty division Fox Searchlight, which acquired U.S. distribution rights for The Wrestler for $4 million in an all-night bidding war after the movie won top honors at the 2008 Venice Film Festival. “They cost a fraction of what studio movies cost, and because the fiscal risks are lower, people get to be creatively reckless. It’s the hallmark of independent film.”

Aronofsky recalls that after Venice, some of the same financiers who had earlier turned him away confided to him that they wished their decisions “didn’t have to be purely dependent on movie stars and could deal with the possibility that a good film could happen.”

Of course, Aronofsky’s best efforts weren’t necessarily destined to be good—an indie film can be just as self-indulgent or plain awful as any studio pic. Still, the studios’ algorithms aren’t fail-safe either. Last fall Warner Bros.’ Body of Lies starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Russell Crowe fell flat at the box office. As of press time, it was too early to predict the eventual fate of Benjamin Button, Gran Torino, Seven Pounds and Valkyrie, all examples of top-notch talent working with every advantage the studios can supply. But insiders have fretted that these films may prove to be too long, too depressing or too overwrought to attract audiences—or to sway Academy voters. It’s one thing that Australia earned just $20 million over the five-day Thanksgiving holiday weekend; studio heads understand that prestige comes at a price. But it’s quite another if the big budgets also fail to return big results on Oscar night—especially if a scrappy upstart runs off with the coveted golden statuettes instead.

One unexpected advantage that independent films enjoy over studio fare is precisely their underdog status. When niche audiences—who are courted through cagey media and marketing campaigns—embrace a film, their word-of-mouth advocacy can help it go mainstream. An informal industry poll published last fall in the Los Angeles Times declared Rice’s Fox Searchlight “the envy of the town” and also singled out Slumdog Millionaire as the film of the season thanks to “the enormous goodwill and lightning-in-a-bottle passion” that could “make this film into a cultural event—you need to have seen it to be cool.” Rice refuses to crow about the praise, but he cautiously explains the appeal of small films that come seemingly from nowhere.

“Audiences hunger for originality,” he says when asked to explain his contrarian’s picks of Slumdog and The Wrestler, which earned Rourke a Golden Globe nomination. “When they discover something—such as a tour de force performance from Mickey Rourke in The Wrestler—people feel compelled to spread the word. Mainstream movies are much more marketing-dependent. You can’t budget for originality.”

Happy-Go-Lucky wonderfully demonstrates that proposition as it follows an unflaggingly optimistic schoolteacher named Poppy going about her rather ordinary life. As plain as that sounds, Hawkins, under Leigh’s direction, creates a potentially career-changing portrait of a complex character.

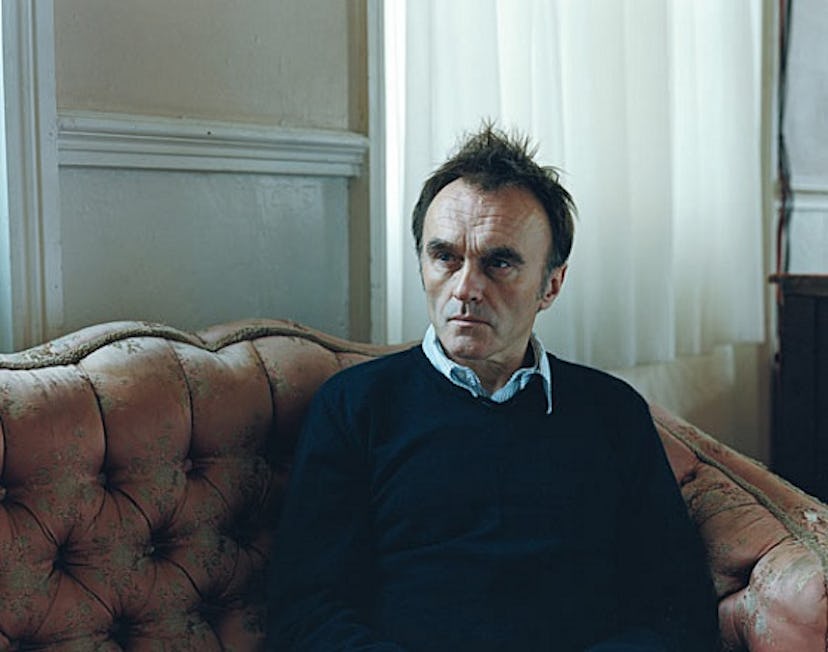

Leigh is the first to tell you that he never expected Hollywood to call, even after such earlier critical successes as Secrets and Lies and Topsy-Turvy. Though he is regarded by his peers as a master filmmaker, his unyielding methods and astringent personality make it a wonder he finds money to shoot films at all. “As you know, the way I develop and make my films is pretty idiosyncratic,” says Leigh, describing with a kind of anarchic glee how he works without a script and forms the characters and story during months-long improvisations with his actors. “I discover what the film really is by going on the journey of making the film.”

Maybe, but raising the money to make that film—about $11 million for Happy-Go-Lucky—can be tough: “People like to know what they’re investing in,” he says. Still, Leigh has come to terms with his artistic bargain, since he refuses to accept easier alternatives such as casting known celebrities. “Why should I?” he demands, bitterly equating such a concession to star appeal with “genuflecting towards Hollywood.”

By comparison, Scotsman Boyle has approached his relationship with the American studio system more pragmatically. A little more than a decade ago, his breakthrough success with the indie classic Trainspotting earned him a chance to join the majors by directing DiCaprio in The Beach. The $55 million budget made for a first-class production, but Boyle recalls a moment when he knew the film had lost its way—and realized there wasn’t much he could do to change course.

“We called it an oil tanker,” he says, looking back. “The Beach was weighed down with impossible wealth, goodness and riches, but trying to turn it around would have taken forever. You just couldn’t do it.” (The Beach disappointed critics and made less than $40 million in the U.S.) Boyle acknowledges that his inexperience and temperament were partially to blame, and that he’s probably better suited to working within tighter constraints. “Some people are great with more, and the more you give them, the better their films become,” he says, citing James Cameron and Ridley Scott as examples. “For me it was more the other way.”

Boyle streamlined for Slumdog Millionaire, taking a nimble team of 10 with him to the chaotic slums of Mumbai, India, though he was abetted by a local crew. A major snag occurred even before shooting began, when a pair of young Indian boys cast in key roles couldn’t act in English. Although Boyle had raised money on the basis of an English-language script, he told his producers—Pathé in Europe and Warner Independent, Stateside—that he wanted to film the children’s scenes in Hindi. Boyle admits the idea must have struck them as crazy, but because only $13 million was at stake, he had just enough personal leverage to squeak the major changes past the moneymen. “I’ve had a couple of hits,” Boyle says with the good cheer of a director looking at his next. “They gritted their teeth and went, ‘Okay.’”

Then in May, Warner Bros. threw the fate of Slumdog into doubt when it axed its two specialty divisions, Warner Independent Pictures and Picturehouse, home to 2007’s Oscar winner La Vie en Rose. “I’m a card-carrying adult, and I love these movies, but it’s never been a high-margin business,” Warner chief Alan Horn told Variety at the time, drawing a hard line between prestige and the profits earned from Warner’s “high-margin” Harry Potter and Batman franchises. Insiders glumly wondered whether other studios would also close their boutique operations to focus on “tent pole” blockbusters as Warner had done. Such an eventuality would hurt independent filmmakers because the studios’ smaller specialty divisions finance projects under their own labels, as Focus Features (a division of Universal Pictures) did with Brokeback Mountain (2005), or buy the distribution rights for films financed outside the studio, as Focus did with Milk when it agreed to pay 50 percent of the film’s financing but only after it was completed. (However they are produced, most indie films rely on the studios for distribution.) That Slumdog was sloughed off by Warner only to re-emerge as a hot property appears to be almost karmic retribution meted out by a puckish film god.

All of which raises a question: Why don’t directors of a certain serious bent just forgo the studios altogether and declare themselves permanent independents like Leigh or Woody Allen, who has been independent since leaving Universal Artists in the Seventies? (His latest film, Vicky Cristina Barcelona, received wide critical praise and took in $70 million worldwide.) “Well, personally I couldn’t afford it,” Aronofsky answers with a laugh, noting that his strategy—one shared by both Boyle and Van Sant, not incidentally—is to alternate between exercising artistic freedom and earning a paycheck. “The Wrestler cost me money to do. I’m not starving or anything, but it’s tough to support a family doing films for nothing.”