George Michael Was an Underrated Pop Virtuoso: An Appreciation of His Musical Genius

From the beginning he was a performance. “George Michael” was a pseudonym, an invention, an imaginative space inhabited by the British pop star originally born as Georgios Kyriacos Panayiotou, who died on Christmas day at the age of 53.

From the age of six, he knew he wanted to perform, and that he wanted to be famous. “I had two very strong ambitions and they’ve always fought against one another,” he told Michael Parkinson in 1998. “One was a passion for music and an ability to communicate through music…and two was this desire to be… filthily famous.” His eventual fame was almost a byproduct of his insecurities, an attempt to totally dissolve his lack of confidence and his low self-esteem. “I was a very unattractive adolescent,” he said elsewhere in 1987. “I had glasses and…you know, spots…I don’t see that person in the mirror anymore, but I know that deep inside I’m still making up for the fat kid.”

Throughout his career he would say in interviews, “It’s not the something extra that makes a star. It’s the something missing.”

Before Wham!, the band he formed with his childhood friend Andrew Ridgeley, Michael had little conception of himself as sexy or sexual. When he saw that his fans had projected a sexuality onto him, he discovered he was also able to use it, manipulate it, and turn it back on his audience. His outfit in the “Faith” video–tight blue Levi’s, a leather jacket, impenetrable aviator sunglasses, a faint cloud of stubble framing his features–wasn’t designed as a “look,” but it became one by virtue of how he moved within it. “I feel that I’m projecting less of an image,” he said at the time. “But it seems to be coming across as more of an image, maybe because it’s more sexual.”

He felt his songwriting was even less calculated than his image, that he wrote pop music not out of some cynical design but from some unexamined inner impulse. “Writing commercial music for me is something that I love to do and it’s totally natural to me,” he said. “It’s not a business process.” He had inherited from Queen and David Bowie a sense of pop as theater, an arena in which to try out different selves.

He had absorbed both the ecstatic and symphonic forms of Stevie Wonder; in his songs with Wham! you could hear the reanimated and slightly altered skeletons of Wonder’s “Uptight (Everything’s Alright)” and “Signed, Sealed, Delivered I’m Yours,” and the songs on his later solo records could exhibit the gravity and symmetry of a composition like “Village Ghetto Land.” His voice, a kind of alpine tenor, had a weightlessness and flexibility to it that enhanced his compositions and, as in “Careless Whisper,” which Michael wrote with Ridgeley in high school, made them buoyant even when they explored the language of despair. In Wham!, Michael wrote the songs and produced the records, and Ridgely contributed, as Michael suggested in his interview with Parkinson, a “sense of humor.”

“We were constantly trying to annoy people,” Michael said. “And that was Andrew all over, like when we were calling the first album Fantastic.”

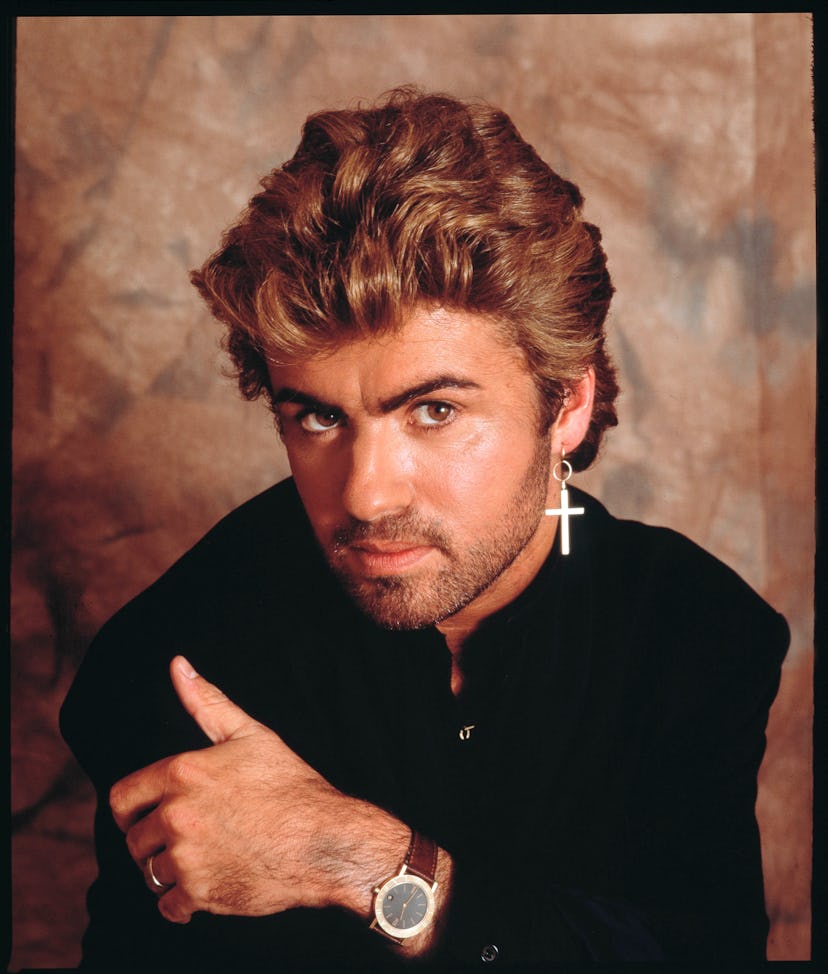

George Michael performing in London, 1988.

Wham! was both annoying and fantastic; they especially lived up to the more traditional sense of the word as they wrote pop songs so bubbly that they seemed to hover somewhere above reality. Their songs were also formally perfect, prismatic creations in the method of ‘60s Motown. “Freedom,” from their second album, 1984’s Make it Big, reached No. 3 on the U.S. charts, and has the insistent pulse and harmonic and melancholic integrity of a Supremes song, but written, sung, and performed by a couple of English kids.

When they disbanded in 1986, after two albums and a world tour, Michael told Jonathan Ross, “There was never any question that we would finish the group before its normal lifespan because it was not a musical entity…It was an image entity…and the image had to be two young guys having a good laugh. When that became boring for us, it was soon going to become boring for other people.”

Michael had also grown exhausted and increasingly emotionally isolated after Wham!’s extensive touring. “When I was younger, because I suppose I was so confused about my sexuality and other things,” he told Parkinson, “I was prone to loneliness and depression around loneliness. Because it is very lonely if you’re surrounded by people but not really surrounded by anyone.”

In the wake of Wham!, Michael composed Faith, which successfully translated him from teen idol to adult pop star. It produced six hits–”I Want Your Sex,” ”Faith,” “Hard Day,” “Father Figure,” “One More Try,” and “Monkey.” As an album, it had an integrity to its design, even as it wandered through genre almost playfully, never failing to use its constituent parts (R&B, funk, dance music, rockabilly, synth pop) as gleaming vehicles for pop.

“I think that I’m already regarded as one of the main pop writers for the Eighties,” he told Rolling Stone in 1988. “But I want to be regarded as that through the Nineties and do something to carry on, something that’s really memorable, so the music becomes something historical. I think that my music deserves it.”

George Michael, “Faith”

When you listen to his albums after Faith, you can feel the significant weight of this burden–especially on songs like 1990’s “Praying for Time,” his own “Love’s in Need of Love Today”–but his pop impulses were never totally submerged in the service of some grander artistic design. His work grew more enigmatic–still recognizably pop, compressions of melody and performance that called considerable attention to themselves, but his compositions seemed to be responding to some internal metric that was somewhat indifferent to the expectations of his critics or his audience.

He titled his second solo album Listen Without Prejudice not as a bid for seriousness (he had already achieved that with Faith) but to focus on the increasing stratification between “black” and “white” music in the record industry. “Rock and roll and soul music supposedly broke down a lot of those barriers,” he told MTV in 1990. “And I think it’s quite disturbing to see the same industries are kind of rebuilding the walls with both hands…and it seems to be profitable for them.” Songs like “Cowboys and Angels” and “Jesus to a Child” assimilated the vocabulary of bossa nova and jazz (the ‘88 Rolling Stone profile features an interlude where Michael enthusiastically plays Getz/Gilberto on a CD Player) and seemed more driven by their subtleties and flourishes than Michael’s vocal performances.

His 2004 album, Patience, featured songs he had labored on for years, and they vertiginously shifted between the personal (“Amazing”) and the political (“Shoot the Dog”), but each song also had an elegance and gleam that were a product of the length of his attention. “Not many people are really that meticulous with what they do I suppose,” he said in a 2011 interview. “I’m just a control freak and terribly afraid of failure or regret so I work very hard at these things.”

Among the things he tried desperately to control was his image. He was a fixture in the English tabloids, which speculated inventively about his romantic life. “A career built over five or six years has got to be stronger than a lie in a newspaper,” he told Ross in 1987. “The same machine or creature that has built my career is I think ruining parts of this country and apparently it’s hell-bent on ruining me.” His sexuality, while always nebulously defined (during the Wham! years and his early solo career he told his friends he was bisexual), finally settled on gay, first privately in 1991 when he fell in love with Anselmo Feleppa, then publicly, in 1998, when a police officer in Los Angeles invited Michael to expose himself in a bathroom in Beverly Hills Park.

Michael was arrested for “engaging in a lewd act”; ever the manager of his own image, even as it seemed to slip away from him, he filmed a video for the single “Outside” in which policemen kissed each other in a bathroom that reassembled itself as a discotheque.

His music videos tend to linger in the public consciousness; he had a gift for crafting images that resonated and reverberated through culture and time. The fluorescent glow of his fingerless yellow gloves in “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go”; the way his hair seemed sculpted into an inflexible continental shelf in the “Everything She Wants” video; the silvery moving dark of the bedsheets in “I Want Your Sex.”

Even when he eventually subtracted himself from his videos, they became defined by his absence and the aura it left behind. In David Fincher’s video for “Freedom ‘90,” supermodels acted as Michael’s avatars, lip-synching the song and drifting through gauzy blue light. Elsewhere, in the corner of a closet, flames consumed Michael’s leather jacket from the “Faith” video. When he finally reappeared in one of his own videos, 1992’s “Too Funky,” he wasn’t the focus of the video but the person behind the camera, filming, once again, supermodels, who seemed to be traversing a catwalk in the uncanny valley, slipping into vehicular and robotic shapes. He had also cropped himself out of his own art as early as the “Father Figure” video, in which he initially appears as a cab driver obsessed with a model, but its focus drifts exclusively toward the model, and to the emotions that flicker across her face between the bursts of a camera flash. There’s the feeling, in these videos, that Michael potentially identified with models, people whose professions required them to be constant subjects of a gaze.

Like a model, he could also be classified as an interpreter of emotion. His own catalog seemed to be in regular conversation with itself, and his tendency to attach timestamps to his song titles either signified an entirely new composition (the two “Freedom” songs), a rerecording (“I’m Your Man”), or faint remixing (“Freeek!”). He embraced sampling and interpolation relatively early in his career; “Too Funky” absorbs the synth scribbles from Jocelyn Brown’s “Somebody Else’s Guy,” and “Fastlove” imports the chorus of Patrice Rushen’s “Forget-Me-Nots” into its ultramodern design.

George Michael, “Freedom ’90”

Listen Without Prejudice centerpiece “Waiting for That Day” lingers in the two chord progression native to The Rolling Stones’ “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” for four minutes before Michael thickly whispers the title of his source material at the end. Later in his career he would completely ingest The Ones’ 1999 house hit “Flawless” and rerelease it with his own digressive melody on the top, one of his many monologues about escape.

His work in this mode reassembled history in fascinating new combinations, which made explicit what even his original productions always were: dazzling assemblages of pop history. There’s the sheer austerity of “Faith,” a Temptations song rerouted through the minimal rockabilly shiver of a Bo Diddley track. There’s “Father Figure,” pop gospel framed by synths that resemble banks of fog. There’s “Praying for Time,” which installs itself in a tradition of political pop; its sentiments are vague (“It’s hard to love / there’s so much to hate / holding on to hope / when there is no hope to speak of”), but it works because of that vagueness. It renders it timeless, capable of fitting into any political atmosphere.

Michael’s songs have a precision and intelligence and a respect for past forms that allow them to converge with and become art, a binary that he knew was false anyway. “If you listen to a Supremes record or a Beatles record, which were made in the days when pop was accepted as an art of sorts, how can you not realize that the elation of a good pop record is an art form?” he told Rolling Stone. “Somewhere along the way, pop lost all its respect. And I think I kind of stubbornly stick up for all of that.”

George Michael in London, May 2011.

He understood the internal mechanics of the songs he covered and registered their movements on a subatomic level. In 1996, at his MTV Unplugged concert, he sang Bonnie Raitt’s “I Can’t Make You Love Me.” He sat on a stool surrounded by concentric circles of musicians–string players, guitarists, percussionists–and he responded sensitively to their dynamics, but still seemed strangely isolated and alone. “I Can’t Make You Love Me,” like his other covers, suggested not only a deep comprehension of the notes and design of the song but of the ache pulsing behind it.

It’s not a “faithful” cover exactly, even as the song doesn’t seem to radically swerve from its native arrangement, but it doesn’t sound like a reanimation of the original text either. “If you don’t, if you don’t love me,” he sings toward the end, his eyes closed, his head swaying as if he were mentally swimming through new angles of feeling in the song.

Even though his voice is smoother and more elastic than Raitt’s, the upper intervals of his voice convey a frailty, a kind of internal shattering, without the substance of his voice ever breaking apart itself. It’s a depthless emotion pressing against an unbreakable surface. A flower blooming in a terrarium. A muffled sob. A flawlessly organized cry.

The Fashion Figures We Lost in 2016

Bill Cunningham, 1929-2016. The father of all street style photographers and his trusty camera obsessively documented both New York society and what people wore on the streets for decades, most notably for The New York Times.

Franca Sozzani, 1950-2016. The Italian Vogue editor redefined what a fashion magazine could be.

David Bowie, 1947-2016. The music legend also helped to push the boundaries of gender through his spectacular wardrobe.

Sonia Rykiel, 1930-2016. The French fashion designer began her career simply because she couldn’t find sweaters she wanted to wear. She soon became the heralded “queen of knitwear.”

China Machado, 1928-2016. The Richard Avedon muse was the first non-white model to appear on the cover of a major American fashion magazine.

Prince, 1958-2016. The purple one had a style all his own, and maintained close friendships with both Gianni and Donatella Versace.

Andre Courreges, 1923-2016. The French designer was the master of 1960’s futurism.

Zsa Zsa Gabor, 1917-2016. The socialite and model was the proto-celebutant.

Nancy Reagan, 1921-2016. During her tenure as First Lady, Reagan maintained a marvelous wardrobe and a busy schedule on both the Washington and New York social scenes.

James Galanos, 1924-2016. The American Couterier’s list of faithful clients included Marilyn Monroe, Nancy Reagan, Ivana Trump, Jackie Kennedy, Lady Bird Johnson, Diana Ross, Judy Garland and more.

Betsy Bloomingdale, 1922-2016. A queen bee of the “ladies who lunch” set, Bloomingdale was married to a heir to the department store fortune.

Richard Nicoll, 1977-2016. The Australian-born fashion designer became a mainstay of the young British fashion scene.

Zaha Hadid, 1950-2016. The world’s most honored female architect also found time for frequent collaborations with the world of fashion.

Aileen Mehle, 1918-2016. Better known by her pen name “Suzy Knickerbocker,” the gossip columnist spread the dirt (or kept the secrets, depending on her mood) of New York Society’s, most recently in the page of W.

Marta Marzotto, 1931-2016. The Italian fashion icon began life in an orphanage, but after a career as a model she married a Count and became a fashion designer in her own right.

Joan Helpern, 1926-2016. – Along with husband David, Helpern owned and designed Joan and David Shoes, high fashion footwear for women on the go.

Fred Hayman , 1925-2016. When he opened Giorgio Beverly Hills it was the first high-end department store on Rodeo Drive, thus earning him the nickname “Mr. Rodea Drive.”