The Protests and Reactions to Dana Schutz’s Painting of Emmett Till in the 2017 Whitney Biennial

The Whitney Museum’s most political biennial in decades is facing a deluge of protests for featuring the white artist Dana Schutz’s painting of murdered black teenager Emmett Till.

“This Biennial arrives at a time rife with racial tensions, economic inequities, and polarizing politics,” begins the wall text that greets visitors immediately as they step onto the fifth floor of the Whitney Museum and into its 78th biennial, which opened last week.

The message, in fact, is found next to a towering painting by the artist Dana Schutz, who, as of this week, is dominating not only the exhibition’s entryway, but practically the entire conversation around it, due to another painting of hers nearby: “Open Casket,” depicting the lifeless face of 14-year-old Emmett Till, based off the photo his mother published in Jet magazine in 1955 to “let people seen what I’ve seen”—that her teenaged son had been brutally murdered for allegedly flirting with a white woman.

Initially viewed as in line with the show’s emphatically political and race-centered works, it is now being subjected to a second wave of reviews and reactions in the form of protests, dismay, and, from what some are posting online, heartbreak at the fact that the museum would showcase a white artist’s appropriation of such an emotionally- and historically-charged image for the black community.

“The painting must go,” the artist Hannah Black wrote in an open letter to the biennial’s staff and curators she published on Tuesday, which not only demands the work’s removal from the show, but its destruction. “The subject matter is not Schutz’s; white free speech and white creative freedom have been founded on the constraint of others, and are not natural rights.”

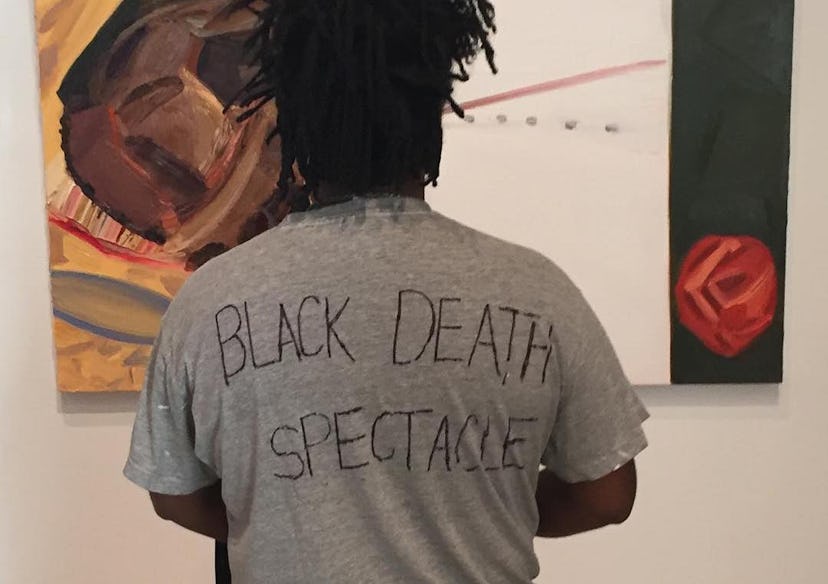

The letter has already attracted signatures of support from art-world figures like Emmanuel Olunkwa and Juliana Huxtable. But the protests actually started when the biennial opened to the public last Friday, at which point some, including the artist Parker Bright, began obscuring the painting by physically standing in front of it, wearing t-shirts with the words “BLACK DEATH SPECTACLE” across the back.

So far, the biennial’s co-curators Christopher Y. Lew and Mia Locks have not issued a formal apology or offer to remove the work from view. They did, however, release a statement to artnet News: “By exhibiting the painting we wanted to acknowledge the importance of this extremely consequential and solemn image in American and African American history and the history of race relations in this country,” Lew and Locks said. “As curators of this exhibition we believe in providing a museum platform for artists to explore these critical issues.”

The statement does not appear to address the primary concern of the protestors—that one of the artists they chose to explore those critical issues is white. However, in a previous interview conducted by the museum’s chief curator and deputy director Scott Rothkopf, and published in the biennial’s catalogue, the matter is touched upon by Locks, who like Lew is Asian-American, in the following passage. She says:

“Thankfully, we’re seeing more and more public conversations about race and structural asymmetries. These issues have been taken up by Black Lives Matter in very significant ways. It’s not always the case in American history, or art history for that matter, that we’ve talked about these conditions in a direct way. This is happening right now, and it feels necessary to declare this as a moment—to think not just about race but about systemic racism, and how the various power structures that are in place are enmeshed. And I would add that a pet peeve of mine is when people assume that artists of color or women artists or those whose identities are more marked would be the only ones to address these issues. In our show, questions of inequity and asymmetry are driven by artists thinking across lines, developing ideas about allyship and coalition politics that go beyond the limited frameworks of the past.”

Lew and Locks met with Parker Bright on Tuesday afternoon to discuss the protests, but did not arrive at any resolution. However, they did have a “very constructive conversation,” Bright said via a video posted to his Facebook page. “One thing that the curators told me is that they were encouraging that type of conversation, that sort of response, which I’m kind of conflicted about because I’m not sure the proper way to have this conversation is to throw black dead bodies in people’s faces, but that’s just the way it is at this point.” He went on: “I don’t think anything is going to be done at this point.”

Schutz, for her part, has said she never intended to sell the work, which she first exhibited in a gallery in Berlin last year. “I don’t know what it is like to be black in America but I do know what it is like to be a mother. Emmett was Mamie Till’s only son. The thought of anything happening to your child is beyond comprehension. Their pain is your pain. My engagement with this image was through empathy with his mother,” she told the _New York Times._ “Art can be a space for empathy, a vehicle for connection. I don’t believe that people can ever really know what it is like to be someone else (I will never know the fear that black parents may have) but neither are we all completely unknowable.”

Of course, these measured responses have not slowed the ferocity of the online response to the exhibition, which was already at high alert thanks to what now feels like a somewhat laughably offensive work: an ultraviolent VR work by Jordan Wolfson. Here is how others have reacted to the Dana Schutz painting of Emmett Till’s murder, so far.

“In the latest case of habitual boundary overstepping and appropriation, painter Dana Schutz’s work Open Casket has sparked controversy and outrage at the Whitney Biennial in New York City … There is sure to be some pushback over artistic freedom, the right to free speech, and whether the entire subject and history of America’s discrimination against people of color should be off-limits to white artists. But this controversy isn’t about rights or freedom. This painting is a prime example of peak whitepeopleing. What is “whitepeopleing”? Whitepeopleing is the privilege and dismissive confidence that you have not only the right but also the permission to do whatever the f–k you want. Whitepeopleing is the audacity of believing that your white hands are gifted with the skill, soul and empathy to transmute the horrific spilling of black blood into something passersby can contemplate before they move on to another sculpture or painting. It is either not knowing or disregarding the difference between a mother saying, “Look what these monsters did to my boy” and a New York paint-slinger saying, “Look what I did.” Whitepeopleing is this.” — Michael Harriot, The Root

“In brief: the painting should not be acceptable to anyone who cares or pretends to care about Black people because it is not acceptable for a white person to transmute Black suffering into profit and fun, though the practice has been normalized for a long time.” — Hannah Black

“Schutz’s painting fetishizes black death and normalizes the violence that black people experience daily. When someone who is wrongfully murdered, whose death is captured on video and then spread virally, whose body risks losing its meaning, a certain numbness is created that we have to be sensitive to and be wary of.” — photographer Emmanuel Olunkwa

I Am an Immigrant: See 80 of Fashion’s Biggest Names Stand Together for Human Rights