One of the biggest quandaries faced by creators in the digital age is that of engagement—of getting people to not just pay attention, but to fully immerse oneself in a piece of media. It’s a difficult trick in an age of constant distraction, of hashtag campaigns and peak TV. Even the biggest artists run the risk of falling into the content machine, its gears grinding fully realized works into animated-GIF and disconnected-lyric pulp.

A week ago, Beyoncé released Lemonade, her sixth full-length album and second “visual album”—each song comes pre-packaged with an accompanying video component, with both mediums presented to the listener/viewer/purchaser as an interconnected whole. The idea of a “visual album,” at least as Beyoncé originally devised it, is not an entirely new concept; artists have paired disconnected clips that pivot off each song’s specific imagery in toto before, although in the years before digital media one would have to buy each segment separately, instead of as one bundle of bits.

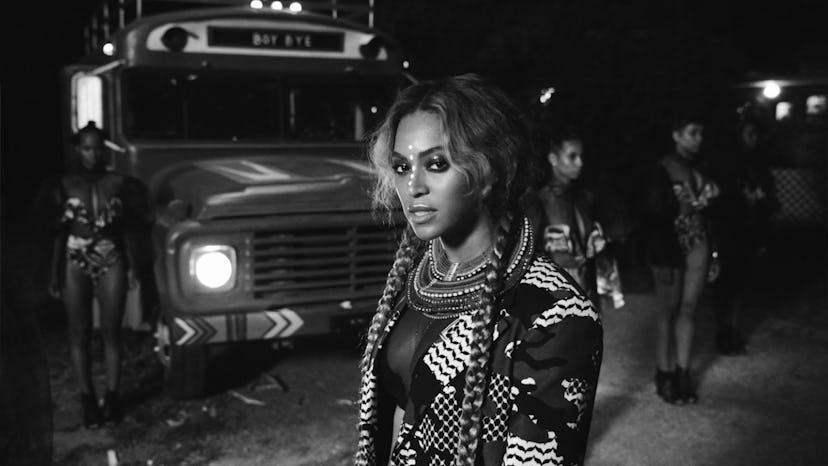

Lemonade, in contrast, is presented as a cohesive whole; it’s a full-fledged concept album about love and loss and, eventually, redemption. Divided into chapters mirroring the Swiss psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s stages of grief—Intuition, Denial, Apathy, Reformation, Forgiveness, Hope, Redemption—Lemonade uses ** gorgeously blunt texts by the Somali-British poet Warsan Shire, arresting shots of the American South, and archival footage from Beyoncé’s own life to depict a journey taken by a character as she veers from the shock of being cheated on to, eventually, peace. It’s a stirring document that could be used as the basis for a syllabus on black American women in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Kanye West might have debuted The Life Of Pablo via simulcast to movie theaters in February, but Lemonade demands to be seen on bigger screens than the phones and tablets its post-HBO viewing has been on. Immersing yourself in the imagery and appreciating the album’s full context demands undivided attention—to spot the “Hot Sauce” inscribed on the bat Beyoncé wields in the joyously destructive romp accompanying the lilting “Hold Up;” or the Nina Simone album that places the quietly mournful “Sandcastles” and Lemonade explicitly in that famed singer’s context; or to study the archival images of black women accompanying the Malcolm X quote (“The most disrespected person in America is the black woman…”) dropped into the middle of the acidic “Don’t Hurt Yourself;” or to look at the mothers of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and Trayvon Martin, shots of whom accompany the mournful “Forward.”

Then there’s the audio-only edition, which can be listened to in pieces, or while distracted. It’s still an incredible document, with Beyoncé drawing on a wealth of collaborators to more fully realize her own sound; it touches on American music genres ranging from Dixieland jazz (the brass on “Daddy Lessons”) to late-night feel-bad R&B (“6 Inch”). Its politics are still present, if backgrounded, although the way in which she owns those idioms that had been claimed by white male rock stars and refashions them in her own image is an unprecendented statement about the politics of rock ‘n’ roll and soul. (The only real misstep is the brief dirge “Forward,” on which the watery vocals of James Blake command the listener’s attention, although his submerged sound at least mirrors the imagery of Beyoncé being trapped underwater that comes onscreen shortly after Lemonade opens.)

Initial reactions to Lemonade showed how the splitting of attention could result in an album’s message being fragmented. The ooh-and-ahh-ing over the possibility that the album’s cheating subplot was taken from real life, ignoring that infidelity is one of the oldest plotlines in the book, rankled; to assume that Beyoncé was being diaristic was more than a bit dismissive of her ability to create art from whole cloth. Beyoncé’s intertextuality with herself has always been present (even on “Daddy Lessons,” she gives the early Destiny’s Child hit “Soldier” a nod), but the disconnect between the public character of “Beyoncé” and the person Beyoncé Knowles Carter is made plain in the film’s credits, where the former is listed as the auteur of Lemonade, and the latter, its executive producer.

Beyoncé’s albums have, over the past few years, become full-on pop-cultural events; even if her songs aren’t getting as much airplay on pop radio as they were a decade ago. (The whitening of top 40 over the past five years especially has been a deplorable trend, particularly when it comes to the shoving aside of black female singers, and Beyoncé’s singles discography is proof of how far that ideology has crept; “Drunk In Love,” from Beyoncé, is her only top-10 single since 2010.) The release of Lemonade was no different; viewers pored over its many references, dissected its lyrics, and analyzed its individual frames with brio, with much of the record annotated by the time the East Coast woke up on Sunday morning.

But with the speeding up of the news cycle comes, well, more news. When Lemonade arrived last Saturday night, music aficionados were still experiencing a hangover from the passing of the Minneapolis-born genius auteur Prince, who had died two days prior; the content fields bloomed with retrospectives of his work, obituaries, and the dam between his prolific back catalog and YouTube being fully breached. Just this Thursday, meanwhile, Views, the new album from the put-upon Toronto MC Drake, came out, providing enough of a frenzy for Snapchat to incorporate coverage of the album’s release into its content plan.

Lemonade, however, has held its own and should continue to among any other major music stories coming down the pike (not to mention items about the increasingly circus-like American presidential election). Not only is it gorgeous to look at – with meticulous costuming and Beasts of the Southern Wild-style shots of trees and lichens that allow viewers to see the way plants, like humans, breathe – its message of black female self-empowerment is one that all Americans should drink in, whether by sitting down with their computers hooked up to their TVs or dancing menacingly to “Don’t Hurt Yourself.”

Watch W’s most popular videos here:

Every Time Beyoncé Slayed in Givenchy

Beyoncé in Givenchy at the 2015 Met Ball.

Photo by Sherly Rabbani and Josephine Solimene.

Jay Z and Beyonce in Givenchy at the 2014 Met Ball.

Photo by Sherly Rabbani and Josephine Solimene.

Beyoncé Knowles in Givenchy Haute Couture at the 2012 Met Ball.

Givenchy by Riccardo Tisci’s silk satin bra and skirt, mink glasses, and necklace.

Marc Jacobs’s silk organza top; Givenchy by Riccardo Tisci’s silk satin bra; Atsuko Kudo’s latex briefs. Prabal Gurung gloves; Marc Jacobs headband; Ofira’s 18k black gold, sapphire, and diamond earrings; Louis Vuitton belt, socks, and shoes; Wolford hosiery.

Beauty Note: Showstopping eyes are easily mastered with L’Oréal Paris Studio Secrets Professional Color Smokes Eye Shadow in Blackened Smokes.

Givenchy by Riccardo Tisci’s angora sweater, crinoline and wool skirt, cap, and shoes. Lorraine Schwartz’s 18k white gold and emerald earrings, David Yurman’s 18k yellow gold and diamond ring.

Beauty Note: Hair stays shiny and smooth with L’Oréal Paris EverSleek Humidity Defying Leave-In Crème.

Beyoncé wears Louis Vuitton’s silk top, cashmere shorts, hat, and mask; Givenchy by Riccardo Tisci’s silk satin bra. Lorraine Schwartz’s earrings, David Yurman’s ring.

Marc Jacobs’s cotton and silk lace blouse; Givenchy by Riccardo Tisci’s silk satin bra; Louis Vuitton’s leather and fur shorts. Marc Jacobs beret; David Yurman’s silver, black rhodium, and diamond earrings; de Grisogono’s 18k white gold and diamond cuff; Givenchy by Riccardo Tisci shoes.