An Afternoon With William Eggleston, Living Icon

A visit with the 77-year old American photographer, whose democratic vision remains surprising and relevant in 2016.

William Eggleston might be one of the only Americans to call 2016 a great year. That’s in large part because he doesn’t vote, a decision the legendary photographer made decades ago. “The last person I would have [voted for] was JFK,” he quipped in his signature Southern drawl in a suite at the Bowery Hotel in New York last week. “But between then and now I didn’t care for the candidates.”

“This year, everything’s coming together,” he said in almost the same breath, about the happy synchronicity of his being honored at the Aperture Foundation’s annual fall benefit, his new exhibition at David Zwirner gallery and re-edition of The Democratic Forest from David Zwirner Books — all this week — and, finally, his good friend Bob Dylan winning the Nobel prize. When I noted that no one has been able to reach Dylan about the prize, Eggleston only said, “That’s typical.” They, of course, haven’t spoken about it, either. “I wish he’d call up,” he added.

Eggleston, however, isn’t one to miss a party. He was in New York from Memphis for a week of dinners, book signings, and events: Monday was Aperture’s benefit dedicated to his pioneering use of color in photography; tomorrow is the opening of his Zwirner exhibition. At 77, he’s still precise about his words and his time. He qualifies nearly all of his answers to questions with some variation of: “From what I know…,” “I suppose,” “I guess,” “Probably,” “Practically,” “Maybe,” or “I don’t think so.” And if he agrees or disagrees, he just might say nothing at all. You could mix a drink during one of his pauses.

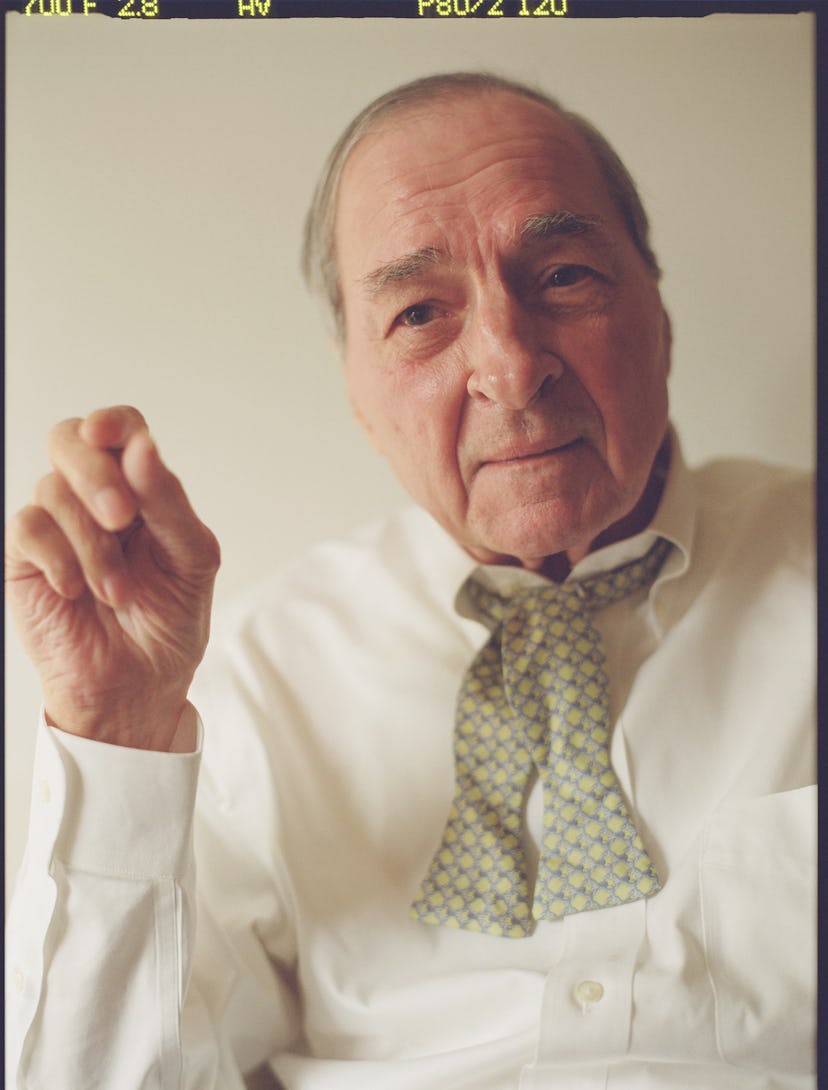

William Eggleston.

As ever, he cut a deliberately dapper figure, dressed for our interview in a crisp white shirt, a patterned ascot tie, and black oxford shoes with a neatly tied bow. “I think one should look great,” he said by way of explanation. He balanced an American Spirit between his ring and middle fingers — he is hardly ever not smoking — and held a Leica m3 that he noted had once belonged to Lee Friedlander. Eggleston still photographs nearly every day. Though his pictures have no particular geographic center of gravity, his own personal mythology still owes much to his time in New York in the 70’s, when he showed the first all-color photography exhibition at MoMA, lived at the Chelsea Hotel, and hung out with the likes of Viva, Patti Smith, and Lou Reed.

To him, New York seems much the same. “I don’t know if it’s really changed that much or not,” he said. “But everywhere has.” Despite his age, and his stated lack of interest in new photography, change has defined the past year of his life. In 2015, his wife of more than 50 years, Rosa, passed away unexpectedly; he had known her since they were children growing up in Southern cotton-growing families. Then this year he made a surprising switch from Gagosian gallery to Zwirner, the latest in a string of high-profile defections from the former dealer to the latter.

William Eggleston.

“When I came out with the latest Democratic Forest… I wanted to show as much as possible of the 10 volumes and Larry Gagosian just didn’t seem to be interested,” he said. “David Zwirner absolutely was. So I said, ‘Well, let’s do it.’”

“The Democratic Forest” is a series Eggleston shot across America from 1983 to 1986, and which was originally published in 1989 with a selection of 150 images from thousands of photographs. Last year, Steidl published a 10-volume box set of about 150 pages each — that’s nearly 1,500 images total. And now David Zwirner Books has published a further selection from “The Democratic Forest,” to accompany the gallery’s show. It helps explain Eggleston’s oft-cited refrain that he doesn’t care about anyone’s pictures except his own.

“That’s the truth,” he declared. “There are plenty of other fine people out there. But I spend most of my time looking at my own things. There’s so many to look at. It takes up a lot of time.”

William Eggleston’s “Democratic Forest”

Untitled from The Democratic Forest, c. 1983-1986. © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Untitled from The Democratic Forest, c. 1983-1986. © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Untitled from The Democratic Forest, c. 1983-1986. © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Untitled from The Democratic Forest, c. 1983-1986. © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Untitled from The Democratic Forest, c. 1983-1986. © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Untitled from The Democratic Forest, c. 1983-1986. © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Untitled from The Democratic Forest, c. 1983-1986. © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Untitled from The Democratic Forest, c. 1983-1986. © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Untitled from The Democratic Forest, c. 1983-1986. © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Untitled from The Democratic Forest, c. 1983-1986. © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Untitled from The Democratic Forest, c. 1983-1986. © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Untitled from The Democratic Forest, c. 1983-1986. © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

The photographs track the automotives of Kentucky, construction sites of Pittsburgh, parked cars of Dallas, and signage of Memphis. These are interspersed with imagery of prep school towns in Massachusetts and apartment complexes in Miami. The tightly composed frames stack textures upon layers of color, but are never cropped, and are shot only once. None of the pictures are named or dated.

The writer Eudora Welty, his late friend, wrote the original introduction to the book in the 80’s, and he quoted her while paging through the new edition. Of an image of a heartland car shop stacked with neon, he recited her line about the top left corner of the image: “Karco illustrates the saturation point of sign-occupied space.”

Eggleston has never been one to to read about photography, however, noting that most critics “talk to hear themselves talk.” He prefers to read technical books about quantum physics. “People I feel I’m closest to would be Stephen Hawking and my deceased friend Carl Sagan. I wasn’t born at the right time to know Mr. Einstein,” he said, with a wry smile. “I think we’re doing the same thing, strange as that sounds. After all the study, images, … [physics] sums up very simply, like [photography], probability. Not to be confused with possibility or what can be accurately predicted. It’s just something that probably will happen.”

William Eggleston.

Photography today is both the most like Eggleston’s work as it ever has been, and the least. The proliferation of camera phones makes the quotidian subject matter he has always favored more accessible; most images we see today were shot only once and in color, his preferred practice. At the same time, if everyone is now a photographer, the importance of getting the image on the first frame, of not cropping, of not editing — all Eggleston tenets — becomes paramount, and have become all the rarer. As photography becomes more and more democratic, it is closer in spirit to Eggleston’s pictures, and farther away in terms of how it gets there.

In the national conversation swelling out of this election year, it’s clear that much of the country Eggleston photographed — the parking lots, diners, and driveways across America — still demands illustration in the imagination of those who arbitrate the cultural conversation. His pictures aren’t political; they are democratic. For all the advances in the medium, for all the changes to the working class, Eggleston’s unbiased and unencumbered photographic vision of the country has stayed so fixedly relevant, and few others have come close to touching him. They are pictures still very worth looking at in 2016.

But as always, Eggleston would rather not read into things too much. When I brought up his longtime association with the American South, he hedged. “It’s been made too much of,” he said. Later, he added, “I’m more a citizen of the world.”

William Eggleston.