Why Alice Neel’s Portraits of Her Neighbors Are What a Divided America Needs Right Now

In a new exhibition at David Zwirner, the writer and curator Hilton Als showcases the late painter’s diverse vision.

In January, two days before Donald Trump’s inauguration, the writer and critic Hilton Als was addressing a crowd of over a hundred when he started to choke up. He had begun to read a quote by the French philosopher Simone Weil as a way of introducing “Alice Neel, Uptown,” the show he curated at David Zwirner gallery, when the themes he’d immersed himself in the last six years in preparation for it struck him—suddenly and all at once—as almost too timely in this “weird political climate.”

Though the late painter is best known for portraits of pregnant women and fellow artists like Andy Warhol, Neel had another side to her work: an appreciation for the many diverse people around her, especially those outside of her own milieu, that has not only spoken to Als since he was a teen, but become increasingly poignant now, in Trump’s America.

So, tucked away in a backroom of the gallery on a recent afternoon, Als again turned to a text to communicate his complicated emotions. “I wanted to read you something,” he said to me, before proceeding to read aloud, off his oversized iPhone, a ‘70s-era quote by a then-72-year-old Neel, in which she was expressing her discontent that critics never acknowledged how she “managed to see beyond [her] own pussy.”

Meet Alice Neel’s Harlem Neighbors, Showcased in “Alice Neel, Uptown”

Alice Neel, “Alice Childress,” 1950.

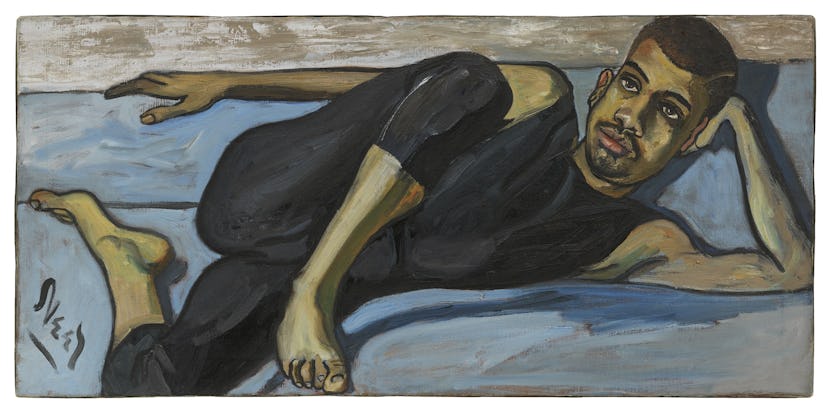

Alice Neel, “Benjamin,” 1976.

Alice Neel, “Black Man,” 1966.

Alice Neel, “Building in Harlem,” c. 1945.

Alice Neel, “Ballet Dancer,” 1950.

Alice Neel, “Harold Cruse,” c. 1950.

Alice Neel, “Ian and Mary,” 1971.

Alice Neel, “Julie and the Doll,” 1943.

Alice Neel, “Ron Kajiwara,” 1971.

Alice Neel, “Stephen Shepard,” 1978.

“What amazed me is that all of the women critics respect you if you paint your own pussy as a women’s libber,” Neel said then. “But they didn’t have any respect for being able to see politically and appraise the third world.”

To Als, this was not the idle talk of a relatively privileged woman atoning for her white guilt. Neel spent the second half of her life immersed in the lives of her neighbors in Spanish Harlem, and has the archives—which Als eagerly mined for the exhibition—to show for it. Starting a few years after she first moved to the neighborhood, on 107th Street, in 1938, she made portraits of seemingly everyone in the neighborhood, from ballet dancers to sociologists. There was, for example, her superintendent’s son; a Vogue design director, Ron Kajiwara, who as a child was detained in a California internment camp; many children who knocked on her door when they found out she painted “Spanish kids”; and public figures like the actor and playwright Alice Childress.

Their stories, thanks to Als’s “detective work,” are showcased alongside their portraits in vitrines containing family photos and other artifacts, and further expanded upon in Alice Neel, Uptown, Als’s forthcoming book. It’s the portraits, after all, that Als has always found the most touching—a celebration of diversity so strong that he originally titled the show “Colored People.” Eventually, though, he decided that was too on-the-nose. Neel was simply painting the people she cared about, without fuss—after all, she always felt more for them than those in her bohemian art world.

That’s something Als can empathize with, and not just because he’s spent so much time uptown at Columbia. Als grew up in Brooklyn, but traipsed all throughout New York with his father, as the only son of West Indian immigrants. “When I first saw her work—this might have been in the late 1970s, when I was not yet twenty—I was immediately consumed by the stories she worked so hard to tell: about loneliness, togetherness, and the drama of self-presentation, spurred by the drama of being,” Als writes in Alice Neel, Uptown.

Alice Neel painting Stephen Shepard.

As it turns out, there are other affinities between the two. There’s an image in the exhibition of Neel in her seventies, standing outside the Whitney Museum, picketing the institution—just three years before it would give her a solo retrospective—for failing to involve people of color in the making of its exhibition “Contemporary Black Artists in America.” Als, too, grew up growing to protests and rallies—something he’s considering picking up again now.

“I think I got sick for three months,” Als said when I asked how he’s been coping. “But this show gives me the courage to keep fighting, somehow.”

Hilton Als at David Zwirner Gallery.

I Am an Immigrant: See 81 Fashion Celebrities Stand Together: