Made In Italy

Alessandro Mendini is best known for his dizzying colors and gaudy motifs. But as a new museum show proves, his work is about far more than fun and games. Alice Rawsthorn catches up with the design maestro.

There are very few, very small spaces between the artfully arranged books, vases, busts, plates, figurines, sketches, paintings, shells, bird’s nests, and other items sitting so elegantly on every surface of designer and architect Alessandro Mendini’s apartment, but he stares forlornly at each of the gaps. “So much is missing,” he says with a sigh, before chuckling. “Though I do know where it is.”

That would be at the Design Museum of the Triennale, the Palazzo dell’Arte in Milan, where Mendini has curated a blockbuster show, “Quali Cose Siamo,” which translates as “The Things We Are.” It consists of what he calls “an anthropological collection” of 800 objects chosen not on the conventional design criteria of what they do or how they look but because, he believes, they tell us what it is like to be Italian. “It’s sort of a personal museum, or a Fellini play, of my vision of Italy,” Mendini explains. All of the exhibits, including the missing loot from his apartment, are jumbled together as if at a flea market: historic and contemporary, expensive and cheap, practical and extravagant.

Among them (although a list doesn’t come close to conveying the ambition and eccentricity of Mendini’s selection) are a giant Campari bottle; pieces of pasta; a Giorgio Morandi still life; the original models of E.T.; an Olivetti Lettera 22 typewriter; a huge Ferragamo shoe; rubble from the 2009 earthquake, which devastated the city of L’Aquila; a replica of Michelangelo’s David; a patchwork jacket worn by the late designer Achille Castiglioni; and a nude portrait of another, Ettore Sottsass.

“It’s just fantastic,” says Australian designer Marc Newson. “Seeing that show is like looking into Mendini’s mind, which is an incredible experience because he’s so humorous, sprightly, and generous. He has such a deep knowledge and understanding of design, and the show reflects that, but it’s also quirky, insightful, and playful. He sees the fun in design, and the poetry.”

Newson isn’t the only fan of the exhibition, which runs through February 2011 and has been packed with visitors since it opened in March, a few weeks before the design world flocked to Milan for the annual Furniture Fair. “I told everyone I could that it would have been better to have canceled the rest of the fair and just held Mendini’s show,” says British designer Jasper Morrison. “It blows away the constricting frontiers of what is generally thought of as design and frees up our thinking about it.”

As if that weren’t enough, Mendini has taken the helm of Domus, the influential design magazine, for a year. He’s also curating an exhibition on Italian craftsmanship, which opens in Verona in September, and completing projects at Atelier Mendini, the architecture practice he runs in Milan with his younger brother, Francesco, including the completion of a vast pavilion for the World Design Capital festival, to be held in South Korea this year. Oh, and he’ll turn 80 next year.

“I’m totally in awe of him,” says Paola Antonelli, the senior curator of architecture and design at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. “He’s so subtle, so innovative, and quite brilliant at crystallizing ideas, although he has never been as well known to the general public as designers like Castiglioni and Sottsass, even in Italy, because he’s at his best working behind the scenes.”

Mendini’s penchant for discretion has made him one of the design world’s well-kept secrets. Aficionados may know that he edited Domus before, during the early Eighties, as well as two other important Italian design magazines, Casabella and Modo. They’ll know too that he was at the heart of Italy’s radical design movement in the Sixties and Seventies and, later, postmodernism. But even if you’ve never heard of Alessandro Mendini, you’re bound to have been affected by his work.

That’s because our lives would be different without him. Mendini has influenced the creation of objects and spaces through his own projects, but his work as a writer, editor, and curator has also had an enormous impact on other designers and architects. The vision he has championed for years—a humane, sensitive, thoughtful, empowering, intellectually rich discipline that’s about ideas, not styling—seems increasingly relevant. It has a special resonance for young designers, who are concerned with cracking environmental problems and imbuing industrial pieces with meaning rather than flipping vertiginously expensive chairs at Sotheby’s or Christie’s.

Mendini has an additional role, as one of the last surviving design maestri, as Italians call the “masters” who made their country the global center of design in the late 20th century. Thanks to “Quali Cose Siamo,” he has moved center stage at a time when Italian design is reasserting itself internationally, with the opening in Manhattan in late September of an American outpost of the Triennale in the space formerly occupied by the American Craft Museum, directly opposite MoMA. The inaugural show will be an homage to Mendini’s own design hero, Giò Ponti, the man he succeeded at Domus. (Mendini paid tribute to Ponti by including one of his paintings in “Quali Cose Siamo.”)

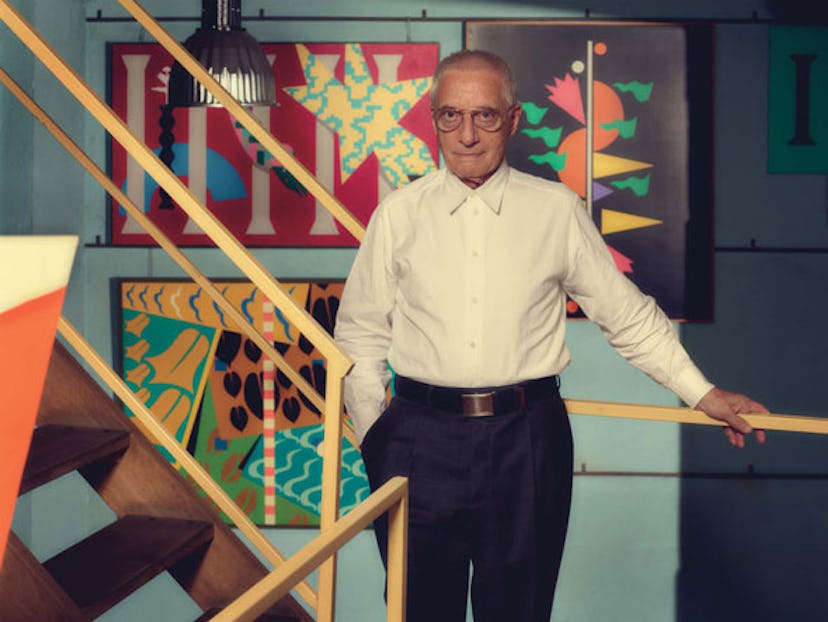

Mention that you’re meeting Mendini, and you’ll invariably be told that he’s very clever, very charming, and very short, with very blue eyes. Quite right. Sitting in the conference room suspended above his open-plan studio, the architect looks impressively lithe, with a light tan and cropped white hair. He stares at you intently through circular wire-framed glasses but rarely ends a sentence without smiling.

“He’s incredibly pleasant to work with, radiating calm and tranquillity,” observes Joseph Grima, who recently left his position as director of Storefront, a nonprofit architecture organization in New York, and moved to Milan to work on Domus’s website; he will take over the magazine from Mendini in February. “He’s also incredibly sharp, one of the most intelligent people I’ve ever worked with, and so open. There’s always a twinkle in his eye.”

The studio occupies what was once workers housing in an old factory on Milan’s eastern outskirts. Mendini and his brother moved there in 1989, when they founded Atelier Mendini. They’ve marked their turf by building a postmodernist folly—a supersize, mosaic canopy in the yard—and filled the studio with posters, architectural models, and objects in the vibrant colors and flamboyant patterns that Mendini loves. (Subtle though he is as a theorist, his physical designs are shamelessly showy.) One room is a workshop for his most famous piece, the Proust chair, a voluptuous armchair with an ornately carved wooden frame and dizzying upholstery that he designed in 1978, and has made in different colors and patterns ever since, often painting them himself. “My friend the architect Gae Aulenti once said that everything I designed looked like Carmen Miranda,” he says with a laugh. “And she was right.”

Mendini lives above the studio. He has painted the apartment in warm colors and filled it with his treasures, but left the structure intact, down to the cheap, gaudily patterned floor tiles. He grew up in far grander surroundings, among the Sironi, Savinio, and other modern paintings collected by his parents in the Milan town house built for them by the rationalist architect Piero Portaluppi. “Perhaps my love of kitsch and vernacular objects was a reaction against the things I grew up with,” he muses.

As a child Mendini loved to draw. Saul Steinberg and Walt Disney were his heroes. But his parents encouraged both him and Francesco to study architecture at Milan Polytechnic. Alessandro then worked in the studio of Marcello Nizzoli, chief design consultant to electronics company Olivetti. (The Lettera 22 typewriter in “Quali Cose Siamo” was designed by him.)

Nizzoli was typical of the first generation of design maestri, including Ponti, and later Castiglioni and Sottsass, who’d trained as architects but turned to product design to help postwar manufacturers persuade the public to pay a little extra for “the Italian line.” This seductive image of la dolce vita sold millions of Fiat cars, Vespa scooters, Flos lamps, and La Pavoni espresso machines. As well as powering the country’s postwar recovery, the “design adds value” formula has been adopted by expanding economies since, from Sixties Japan to China today.

Italy was lucky in that Nizzoli, Castiglioni, Sottsass, and their fellow maestri were unusually thoughtful and imaginative about their work, and that Ponti contextualized it so sensitively in Domus. Italian design emerged with an intellectual depth that was lacking in most other countries, where design was relegated to a grubbily commercial role, as a poor relation of art.

Mendini’s generation of architects and designers, who were born in the Thirties—a decade or so after Castiglioni and Sottsass—and were children during the Mussolini regime and World War II, grew up in this rich, provocative visual culture. Steeped in counterculture politics, they were less comfortable with design’s role as a catalyst for consumerism than their predecessors. By the late Sixties Mendini was embroiled in Italy’s “radical design” movement, in which groups like Archizoom and Superstudio in Florence treated their work as a conceptual tool to challenge the establishment by developing utopian projects.

In 1970 he joined Casabella, where he followed Archizoom, Superstudio, and empathetic designers like Sottsass and Gaetano Pesce, as well as emerging postmodernist design groups in the U.S. and Austria. While at the magazine, he assembled a crack team. The art critic was Germano Celant, who later became senior curator of contemporary art at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, and is now curating the Ponti retrospective at the Triennale in New York. (Celant coined the term arte povera to describe the work of Michelangelo Pistoletto, Alighiero Boetti, and other post-Pop artists whose work he championed in the magazine.) “Casabella was amazing,” Antonelli recalls. “Everything about it was so strong—the covers, the ideas, everything—because Mendini was always pushing it forward.”

By the late Seventies he was doing the same at a new magazine, Modo, and had established himself as a conceptual designer producing work that critiqued commercial design culture. One key example is 1974’s Lassù, for which he mounted a wooden chair on a pedestal and filmed its destruction by fire. For 1978’s “Redesign,” he transformed classic modern chairs into self-parodies. Clouds painted in gaudy colors were attached to Marcel Breuer’s Wassily chair, and the back of Gerrit Rietveld’s Zig-Zag chair was enlarged to form a cross. Avant-garde designers have toyed with similar ideas ever since, and none of Mendini’s Seventies projects would look out of place in one of the current crop of “critical design” shows.

Nor would the pieces he produced for Studio Alchimia, the design group he formed with Sottsass and other friends in 1979. Their aim was to humanize industrial design at a time when modernism seemed intellectually spent. It was during this period that Mendini unleashed his inner Carmen Miranda, and poked fun at the modern movement by violating its proscriptions against bright colors and exaggerated contours, with the creation of vivid-hued objects with theatrical shapes and kitsch motifs, often made by hand. Jasper Morrison saw an Alchimia show during a student trip to the 1979 Milan Furniture Fair. “I was dazzled,” he says. “It was obvious that Mendini was a mischievous, highly intelligent, and radical designer, and that Studio Alchimia produced much more than textbook examples of design.” You can still see the influence of Mendini’s style on the flamboyant objects by theatrical young designers like Jaime Hayon and the duo behind Studio Job, Job Smeets and Nynke Tynagel.

Alchimia’s work culminated in “The Banal Object,” an exhibition at the 1980 Venice Biennale, but Sottsass soon chafed against the group’s anticapitalist ideals. “He always wanted to talk about money, and Alchimia wasn’t a place where you could do that,” says Mendini. “So he left and started Memphis. Sottsass said, ‘Are you coming with me or not?’ And I said, ‘No, I’ll stay with Alchimia.’ But I did design something for the first Memphis collection. Up until then we’d been friends, and spoken every day. I always remained friends with Sottsass—I’m not capable of making enemies—but he didn’t remain friends with me. Though we became friends again when Memphis ended.”

Design snobs often argue that Memphis was a mediagenic, commercialized version of Studio Alchimia. In many respects it was, but a stupendously successful one. There were long lines outside its launch party at the 1981 Milan Furniture Fair, and the photographs of Sottsass, then in his 60s, surrounded by his young collaborators in a boxing ring–shaped “conversation pit” created by Japanese designer Masanori Umeda, were published worldwide. Until then the postmodernist theories developed by Mendini and others had seemed incomprehensibly complex for the public, but they made instant sense in the form of Memphis’s cartoonish furniture. Pastiche became the defining design style of the Eighties, from Philippe Starck’s restoration of the Royalton Hotel in New York to Karl Lagerfeld’s reinventions of Coco Chanel’s boxy suits.

Mendini charted postmodernism’s progress in a new role at Domus. By positioning design and architecture at the intersection of art, literature, philosophy, politics, fashion, and pop culture, and analyzing them all with equal rigor, he created a scintillating editorial mix of highbrow and lowbrow—an innovation that is now mainstream. Another new concept, at least in the scholarly world of architectural publishing, was to splash photographs of architects and designers, often shot against surreal backdrops, on the cover. Mendini’s editorial instincts were fantastic. Both Zaha Hadid and Frank Gehry appeared there, when they were barely known, even within their own profession.

“Domus was the bible,” says Newson, who discovered it as a design student in Sydney when working part-time at a news agency. “A couple of subscription copies were air-freighted in every month for a ridiculous amount of money. I used to ‘borrow’ them, and they were my windows into the world of design.”

Mendini left Domus in 1985 to focus on a new commercial role as creative director of Alessi, the Italian home-products company. A few years later he took on the same position at Swatch, the Swiss plastic watchmaker. Designing stores and products for both companies introduced him to the mass market, and enabled him to help younger designers. “He put me up for a job at Swatch when I was a complete and utter nobody, and frankly too inexperienced to do it,” recounts Newson. “Mendini recommended me to other companies, too, and always had a nice thing to say about my work. There are plenty of grumpy old men in design, but he’s the absolute opposite.”

With his brother, Mendini completed his most ambitious architectural project, the Groninger Museum in the Netherlands, a postmodernist palace that they developed from 1989 to 1994. He has since worked on everything from a toaster and a juicer for Philips to McDonald’s Italian headquarters and a satellite museum for the Triennale in Seoul while producing a steady stream of exhibitions, essays, and sketches. Whenever a new design debate has unfurled, Mendini has participated, often from the start, and always elegantly.

Typical was his critique of Lasting Void, a resin and fiberglass seat cast inside the cavity of a dead cow by the young German designer Julia Lohmann. Her objective was to force people to confront the exploitation of animals by industry, but Mendini saw the piece as unnecessarily cruel and trite. He said so in a letter, which was published in several design magazines in 2007 alongside Lohmann’s response. After reading her explanation, he e-mailed her saying he had changed his mind, and hugged her when he saw her in Milan the following year. “The meeting was quite emotional,” Lohmann recalls. “The letter from him was a very good challenge for me. It helped me to clarify my position by questioning myself more thoroughly.”

Prolific though he has always been, Mendini remained largely out of the limelight until this spring, when the opening of “Quali Cose Siamo” coincided with his return to Domus. His second stint there has been as iconoclastic as the first but for very different reasons. During his first editorship, Domus was thrilling and audacious; now it is studiedly quiet and calm, in stark contrast to the hysteria with which other magazines are responding to the digital threat.

“This time his Domus is very dignified, very rarefied, quite meditative,” says Grima. “It looks back to his Domus of the Eighties, and the early Domus of the Thirties. The typeface he chose is Futura, which is typical of Italian graphic design in that period. His editorial is in the form of a diary, the thoughts of the moment, which are articulated throughout the magazine. That’s the only consideration for him. He would never sacrifice it to chase exclusives.”

The new Domus covers are delicate portraits drawn by graphic artist Lorenzo Mattotti. A recent cover star was Sigmund Freud, used to illustrate a piece on what Mendini calls the “psychological interiors” of his study in Vienna, as well as Ludwig Wittgenstein’s home there, and the House of Glass designed by French architect Pierre Chareau in Paris. “At this point I am interested in thinking more deeply about the future, beauty, and quality,” he explains. “Editing Domus for a year is an opportunity to do that.”

When asked what interests him in contemporary design and architecture, he winces. “I find it completely impossible to answer that question,” he says before citing the “highly aestheticized minimalism” of French product designers Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec and British architect David Chipperfield. He’s also intrigued by the Green School, a progressive educational facility in Indonesia that was built—and is constantly rebuilt—from locally grown bamboo.

Once the year at Domus is over, he plans to devote more time to writing, curating, drawing, and design. “I’m just not capable of concentrating on one thing—Ponti was the same,” says Mendini. “You know, I’ve been a pessimist my whole life, but now I’m optimistic. The world is so violent that I feel it’s my responsibility to find something positive. At my age optimism is essential.”

Alessandro Mendini

1974’s Lassù, a performance piece

Alchimia’s Kandissi sofa, 1979

Scivolando chair, 1983

The Groninger Museum, in Groningen, Netherlands

Alessi corkscrew, 2003

The Cartier column, Art Basel, Switzerland, 2009

A redesign of Gerrit Rietveld’s Zig-Zag chair, 1978

Rousseau vase in fiberglass, 2007

Paradise Tower, Hiroshima, Japan, 1989

A redesign of a Forties chest, 1978

Drawings by Mendini for Milan’s Triennale design museum

A performance piece for Casabella, 1975

Senza Titolo, lacquer on wood, 1996

Mendini’s installation at the Triennale.