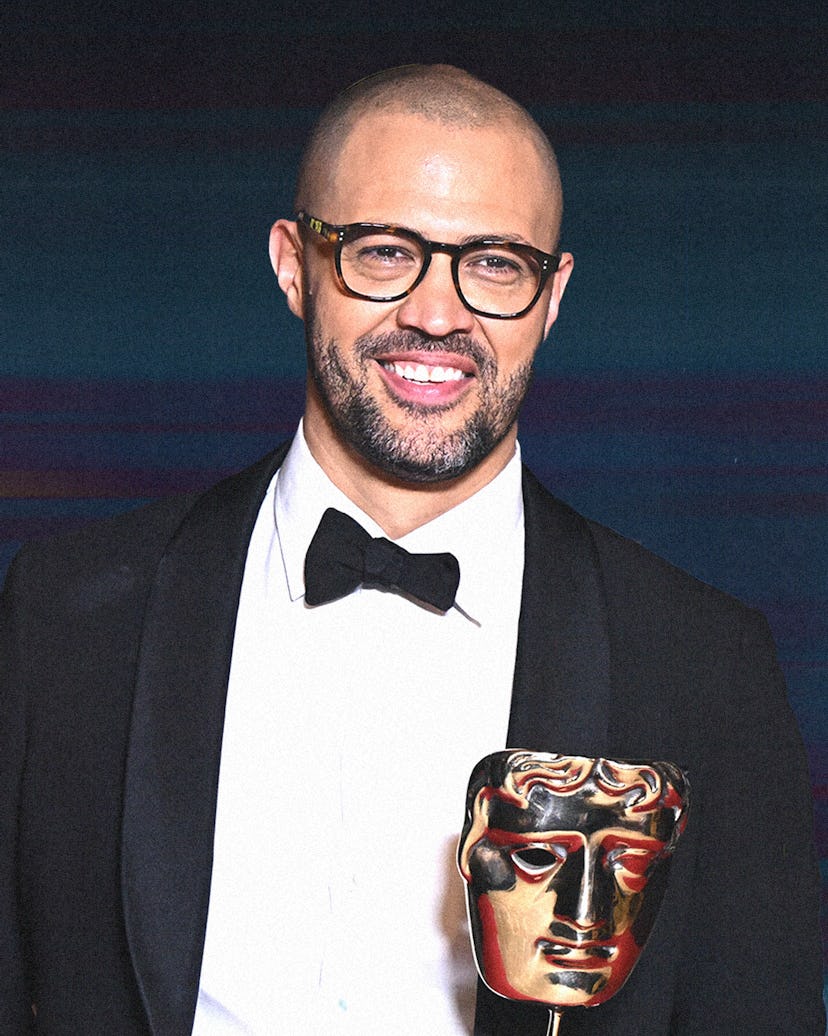

American Fiction Director Cord Jefferson on Going From Gawker to the Oscars

Cord Jefferson did not watch the Academy Awards nominations ceremony. “I have such severe anxiety,” the writer-director behind breakout dramedy American Fiction recently told W over the phone, “that I was worried that if I watched it live, I would pace a hole in my living room floor or have a heart attack. Maybe both.” Jefferson took a Xanax and tried to sleep through it instead, but when he woke up the next morning to 228 unread text messages, he knew “that either something terrible had happened or something really good. Fortunately, it was the latter.”

It turns out the 42-year-old debut director had no reason to worry. Ever since winning the coveted People’s Choice Award at TIFF 2023 (and now, the BAFTA for Best Adapted Screenplay), American Fiction has been a heavy Oscar contender. Based on Percival Everett’s 2001 novel Erasure, the film stars Jeffrey Wright as Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, an erudite college professor and novelist who, in retaliation to complaints from publishers that his work is “not Black enough,” writes a stereotype-laden book about a Black boy in the ghetto. To his dismay, it becomes a hit.

As a journalist-cum-TV writer, Jefferson never exactly planned to direct his own films. He was an editor at the now-defunct Gawker until 2016, before transitioning to writing for television, starting with Comedy Central’s The Nightly Show With Larry Wilmore. That turned into gigs writing for series like Master of None, The Good Place, Succession and Watchmen, for which he won an Emmy in 2019. After reading Erasure—and finding in it a story that felt “written specifically for me”—the screenwriter decided to try his luck behind the camera—and now, just five years after that Emmy win, American Fiction is nominated for five Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Adapted Screenplay.

For the most part, Jefferson is still adjusting to this new normal. Days before we spoke, he had attended the Oscars Nominees Luncheon, where he was still in shock to be sitting between Thelma Schoonmaker, America Ferrera, and the Chief of the Osage Nation. “Even Robert Downey Jr. was coming up saying he loved the movie,” Jefferson exclaims. “It still feels like a dream.”

Jeffrey Wright brings such life to this role. When did you know he was your Monk?

I’ve been obsessed with Jeffrey ever since I saw him in Basquiat when I was in high school. I started reading the novel, Erasure, in Jeffrey’s voice. I have no idea why, but that’s how early I started thinking of him. Jeffrey was the only option. I sent him the script like, “Listen, man, I have no Plan B. This is written for you, so please say yes.” Saying you’re desperate in your opening salvo is not the best negotiation strategy, but I did.

Jeffrey Wright as Monk in American Fiction

You said you decided to direct the film only after realizing that your screenplay would feel too personal to give away. Had you considered directing before that?

No. When I was working on Master of None, Aziz Ansari said, “Have you ever thought about directing?” I said, “No, I like to write, and I’ve never been to film school.” He was like, “I went to NYU for business school and I was nominated for a Golden Globe for directing last year!” So he planted that seed. But I told myself to wait for something that felt like I could direct as well, if not better, than anybody else on the planet. I found that when I read this novel. Even besides the satirical side about the limitations people put on Black writers and stories, I saw overlaps between Monk’s life and mine. I have two siblings, with a push-pull dynamic. We have an overbearing father figure. My mother didn’t die of Alzheimer’s, but she died of cancer, and toward the end of her life, I moved home to help take care of her. There were all these strange similarities, and it felt like I understood this story on such an intimate level. That’s what finally gave me the courage to direct.

What was a harder transition: going from journalism to writing for TV and film, or from writing to directing?

Writing, to me, is writing. For James Baldwin, writing was a toolbox that allowed him to do a lot of different things: he’d write a book of essays, then a novel, and then a journalistic article about politics. The first draft of the script for Spike Lee’s Malcolm X was by James Baldwin! If you’re a good journalist, you can probably be a good screenwriter or novelist. That skillset travels. There’s a steeper learning curve from writing to directing, but maybe not as steep as you think. I realized that when I’m writing a scene, I was already thinking about what the characters are wearing, how I want them to move around the space, enunciate or tell a joke. I just had to articulate those ideas to a cinematographer, a costume designer or a production designer.

You worked on Watchmen and Station Eleven, two TV show adaptations that play very liberally with their source material. What did those shows teach you about the art of adaptation?

Watchmen was probably the most revelatory because it was the first. Everything that happened in the original comic was part of our show, but we were inventing brand-new characters and entirely new scenarios. Approaching that, [writer] Damon Lindelof said, “You don’t have to hew so closely to the text, but you need to hew closely to the feelings and emotions and spirit of Watchmen.” That was a real lesson in what I should aim for in a good adaptation, and one of the things that Percival told me he likes about it. He said, “You didn’t make a carbon copy. You used something that is an inspiration for you, but you’ve made a brand new piece of art that stands on its own two feet.”

Jefferson on set with Trace Ellis Ross, who plays Monk’s sister

Monk ends up on the same voting committee as his nemesis, Sintara (Issa Rae), leading to her pushing back on Monk’s philosophy about Black literature. In the book, however, the two never interact. Did you make that change because you wanted his worldview to be challenged?

Yes! When I was reading Erasure, I was looking forward to the moment when Monk would meet his foil. But then, it never came. When I sat down to adapt, I knew that scene had to go in there—where you have these two really smart people dissecting their ideological interpretations of art and work and Blackness. One of the things I like about that scene is that Monk finds himself on the back foot, and realizes that this person he thought was stupid and reckless is thoughtful, formidable, and smart. I feel like every argument in a movie should be a draw. There shouldn’t be a winner. I wrote the scene and I don’t fully know who I agree with!

That’s the beauty of it!

The point that Sintara makes is, “Look, I am making art within a series of institutions and in a society that made these rules generations before I was around.” In my life, it was a real growth period when I realized that I shouldn’t be mad at individual artists. I used to be like, “Whoa! Why is this person making this art? This is bad! Aren’t they disappointed in themselves?” But then I realized a better, more complex, and harder question to ask is, “Why are the people atop these institutions—the publishers and TV and movie [executives]—so interested in greenlighting the same stories about Black life, and about buying these tropey stories, over and over?” It was important that Sintara reflect that idea.

Issa Rae as Sintara

It was just announced that you’ll be writing a new series adaptation of Just Cause, starring Scarlett Johansson in her first television role. How exciting is that?

Thrilling, man! I’ve sold multiple TV shows, but every project has died somewhere. It had been six years of trying unsuccessfully to get my own thing going, and the last time was this Apple show that was very close to getting on the air, then didn’t. I was down in the dumps and looking for something to read over the holiday break, and that’s when I picked up Erasure. Had that Apple show gone [through], I would’ve been in pre-production and wouldn’t have read it. I wouldn’t have written this script. I wouldn’t have been directing, because they wouldn’t have let me direct one of those episodes. It’s nice to remember that, even in your deepest failures, there might be something good around the corner. It was like two months after I had my TV dreams dashed that I found this book. Now, I’m making a TV show. I’m thrilled to finally be here.

American Fiction is now in theaters and available to stream on Amazon Prime.